Foundatio ns

Why Britain has stagnated

Setting the scene

Here are some facts to set the scene about the state of the British economy.

- Between 2004 and 2021, before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the industrial price of energy tripled in nominal terms, or doubled relative to consumer prices.

- With almost identical population sizes, the UK has under 30 million homes, while France has around 37 million. 800,000 British families have second homes compared to 3.4 million French families.

- Per capita electricity generation in the UK is just two thirds of what it is in France (4,800 kilowatt-hours per year in Britain versus 7,300 kilowatt-hours per year in France) and barely over a third of what it is in the United States (12,672 kilowatt-hours per year). We are closer to developing countries like Brazil and South Africa in terms of per capita electricity output than we are to Germany, China, Japan, Sweden, or Canada.

- Britain’s last nuclear power plant was built between 1987 and 1995. Its next one, Hinkley Point C, is between four and six times more costly per megawatt of capacity than South Korean nuclear power plants, and one-and-a-half times as expensive as those that South Korea’s KEPCO has agreed to build in Czechia.

- Tram projects in Britain are two and a half times more expensive than French projects on a per mile basis. In the last 25 years, France has built 21 tramways in different cities, including cities with populations of just 150,000, equivalent to Lincoln or Carlisle. The UK has still not managed to build a tramway in Leeds, the largest city in Europe without mass transit, with a population of nearly 800,000.

- At £396 million, each mile of HS2 will cost more than four times more than each mile of the Naples to Bari high speed line. It will be more than eight times more expensive per mile than France’s high speed link between Tours and Bordeaux.

- Britain has not built a new reservoir since 1992. Since then, Britain’s population has grown by 10 million.

- Despite huge and rising demand, Heathrow annual flight numbers have been almost completely flat since 2000. Annual passenger numbers have risen by 10 million because planes have become larger, but this still compares poorly to the 22 million added at Amsterdam’s Schiphol and the 15 million added at Paris’s Charles de Gaulle. The right to take off and land at Heathrow once per week is worth tens of millions of pounds.

- The planning documentation for the Lower Thames Crossing, a proposed tunnel under the Thames connecting Kent and Essex, runs to 360,000 pages, and the application process alone has cost £297 million. That is more than twice as much as it cost in Norway to actually build the longest road tunnel in the world.

These are not just disconnected observations. They highlight the most important economic fact about modern Britain: that it is difficult to build almost anything, anywhere. This prevents investment, increases energy costs, and makes it harder for productive economic clusters to expand. This, in turn, lowers our productivity, incomes, and tax revenues.

Everyone reading this will already be aware of the country’s present economic sclerosis. Real wage growth has been flat for 16 years. Average weekly wages are only 0.8 percent higher today than their previous peak in 2008. Annual real wages are 6.9 percent lower for the median full-time worker today than they were in 2008. This essay argues that Britain’s economy has stagnated for a fundamentally simple reason: because it has banned the investment in housing, transport and energy that it most vitally needs. Britain has denied its economy the foundations it needs to grow on.

From 2010 to the summer of 2024, Britain was run by Conservative-led or Conservative Governments. The Conservatives are the traditional party of business, and in the 1930s and 1980s they pushed through reform programmes that successfully renewed Britain’s economy. Virtually any Conservative minister from the past fourteen years would speak warmly about that heritage if asked, and would express the hope of being its inheritor. And yet, with honourable exceptions, the governments of the last fourteen years failed in this vocation. Failing systems remained unreformed, continuing to stifle Britain’s prosperity. Today Britain is ruled by a Labour Government that recognises this failure to build, and which has articulated high ambitions for changing this. But it remains doubtful that they will be any better at delivering on those ambitions than the Conservatives were.

Constitutionally, British governments have immense power. How has a series of governments with both the will and the means to deliver systemic reform failed to do so? How can it be that the overwhelming experience reported by former ministers and advisors is one of disempowerment – of a ‘blob’ operating beyond their control, of pulling levers and nothing happening, of a vast dysfunctional machine slowly disintegrating on autopilot?

We believe that Britain’s political elites have failed because they do not understand the problems they are facing. No system can be fixed by people who do not know why it is broken. Like the elites of Austria-Hungary, Qing Dynasty China, or the Polish Commonwealth, they tinker ineffectually, mesmerised by the uncomprehended disaster rising up before them.

If any government, Conservative or Labour, wishes to use its powers to improve the country, it needs to understand which of Britain’s institutions have failed, and why they have done so. Only then can they begin to develop a systematic programme of reform that will restore Britain’s economy to strength and its society to vitality. The alternative is continued drift, relative decline, political disenchantment, and a nation unable to meet the great challenges of our time. This essay is a first attempt at offering such a diagnosis.

Falling behind

Britain is a country of immense achievement. For most of modern history, its people were the richest, healthiest and best educated in the world. Its housing stock and its infrastructure was far more advanced than those of any of its rivals. It led the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions. Its institutions were almost uniquely liberal. Though British history contains its share of missteps and tragedies, there is probably nowhere else on earth that matches its achievements since the mid-eighteenth century, relative to its size and resource endowments.

Many of these underlying strengths remain. The British people value debate and heterodoxy. They respect science, law and institutions. In hours of crisis, like the Russian invasion of Ukraine, they display unity and good sense. However inefficient and dysfunctional they may be, British institutions are strikingly incorruptible. One of the scandals of the decade is the alleged embezzlement of a campervan, an offence that would surely bring a contemptuous smile to the lips of a Putin or a Berlusconi.

Despite these strengths, Britain is falling behind the developed world in economic dynamism. It led the world in the nineteenth century, and then Europe during the first half of the twentieth, but it lost its leadership after the Second World War. Since 2008, it has been clearly underperforming most of the developed world, even some of its more heavily taxed and regulated continental neighbours.

Most popular explanations for this are misguided. The Labour manifesto blamed slow British growth on a lack of ‘strategy’ from the Government, by which it means not enough targeted investment winner picking, and too much inequality. Some economists say that the UK’s economic model of private capital ownership is flawed, and that limits on state capital expenditure are the fundamental problem. They also point to more state spending as the solution, but ignore that this investment would face the same barriers and high costs that existing infrastructure projects face, and that deters private investment.

Others believe that our ageing society means permanently lower growth and higher taxes. Dietrich Vollrath’s book Fully Grown: Why a Stagnant Economy is a Sign of Success says that slower growth is an inevitable part of becoming services-driven (and of birth rates declining). Another school of thought sees Britain’s 2010s performance as ‘one thing after another’, with a slow recovery from the financial crisis followed by Brexit, followed by Covid.

But all of these explanations take the biggest obstacles to growth for granted. Our economy isn’t growing for the same reason that no more planes take off or land at Heathrow today than did twenty years ago: at some point it becomes impossible to grow when investment is banned.

Over the past two decades, Britain’s economy has needed a huge quantity of new housing, transport infrastructure and energy supply. Its postwar institutions have manifestly failed to deliver these. Britain is now a place in which it is far too hard to build houses and infrastructure, and where energy is too expensive. This has meant that our most productive industries have been starved of the resources, investment and talent – the economic foundations – that they need to grow.

The UK faces other challenges besides these. Our healthcare and higher education systems are so broken that politicians elected on a clear mandate to cut migration instead let it rise to unprecedented levels to keep them afloat. Crime, though it has been falling for years, is substantially higher than it was in pre-Second World War Britain, despite a far older population. It is also significantly higher than in many other European countries including the Netherlands, Spain, Austria, Switzerland, Norway, and Italy. Childcare is so expensive that many families have fewer children, and later in life, than they would like. Our tax system is riddled with distortions and perverse incentives. There is no consensus about what our higher education system is supposed to do, who should benefit from it, and who should pay. And our political institutions are sclerotic: at best, many are unable to perform their most basic functions; at worst, they are a huge barrier to innovation and effective governance.

But these other challenges do not explain why a huge economic gap opened up between us and other leading economies, since problems in immigration, crime, childcare, tax, and political institutions are also found in exactly the countries that have pulled away from Britain economically since 2008. Nor can austerity or the hangover from the financial crisis explain Britain’s malaise. The financial crisis was at least as turbulent in the United States as here. And austerity was at least as tough across Europe, which also had to fend with the euro crisis.

The Office for Budget Responsibility’s estimate of the impact of Brexit says that it will knock four percent off long-run UK productivity. This would be very painful, but still only a small fraction of the growth we have missed over the past fifteen years. (It also does not factor in the positive effect of avoiding destructive regulations like the EU Artificial Intelligence Act and Digital Markets Act.)

Britain’s startling underperformance more recently is explained by the more basic factors this document focuses on: preventing investment into housing, infrastructure, and energy supply.

Prosperity is intrinsically important. It gives people security and dignity, leisure and comfort, opportunity and economic freedom. It gives us freedom to pursue our other national goals: caring for older and less fortunate members of society, upholding a law-governed international order, preserving and enhancing our landscapes and townscapes, and leading the way in world-changing scientific research.

But there is even more at stake here than that. We noted above the enduring strengths of the British social settlement – responsibility, autonomy, love of debate, respect for the individual. Economic failure saps confidence in these things. It begets dependency, resentment, defeatism, division and bitterness. It turns win-win relationships into zero-sum ones, where someone else must fail for you to succeed. Economic reform is not only the key to prosperity: it is the key to preserving and amplifying what is valuable about our society itself.

A short history of British productivity

Britain’s biggest problem is its low productivity – that is, the value of the goods and services people produce per hour they work. Before the pandemic Americans were 34 percent richer than us in terms of GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power, and 17 percent more productive per hour. (Purchasing power parity, or PPP, attempts to account for differences in purchasing power between countries, rather than just using exchange rates). The gap has only widened since then: productivity growth between 2019 and 2023 was 7.6 percent in the United States, and 1.5 percent in Britain. This is not a general Western European problem either: the French and Germans are 15 percent and 18 percent more productive than us respectively.

Historically, this is exceptional. For most of modern history, Britain has been more productive than its peers, and when it has started to fall behind, it has successfully reformed itself to regain its advantage. Between the mid-eighteenth century and the late nineteenth century, Britain was the world’s leading economy. Though it was overtaken by the United States by the beginning of the twentieth century, it remained Europe's leading economy until the early 1950s, with the continent’s highest productivity and living standards, and its most advanced innovating firms.

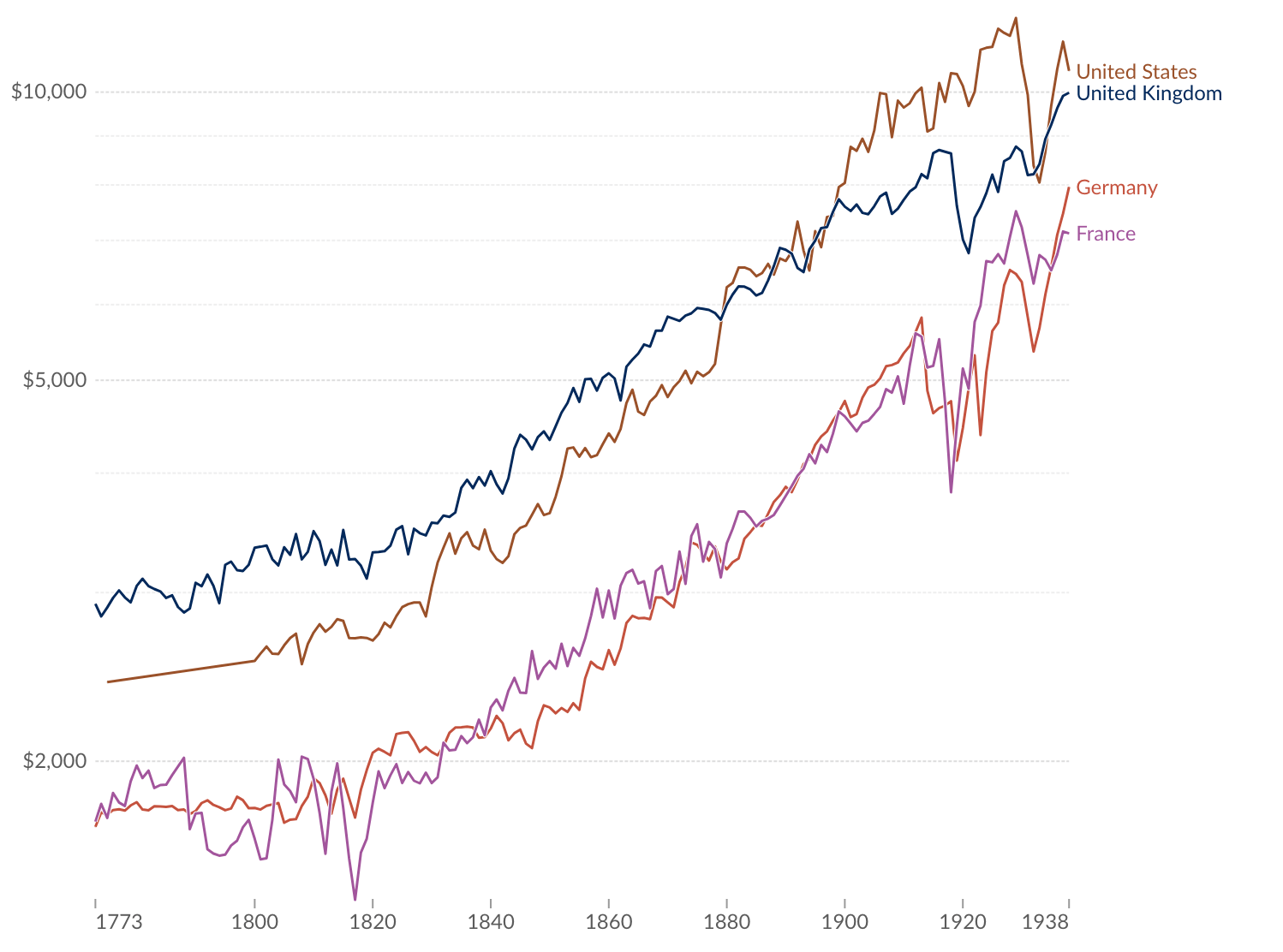

Output per capita, current prices, 1773-1940. Britain led the

world until taken over by the USA. But it still led Europe at the

beginning of the Second World War.

Output per capita, current prices, 1773-1940. Britain led the

world until taken over by the USA. But it still led Europe at the

beginning of the Second World War.

But the reforms of the late 1940s, largely under Clement Attlee’s governments, caused Britain to grow more slowly than any other major European country and the US until the mid-1980s. Britain was overtaken by Germany, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark, Italy and Switzerland.

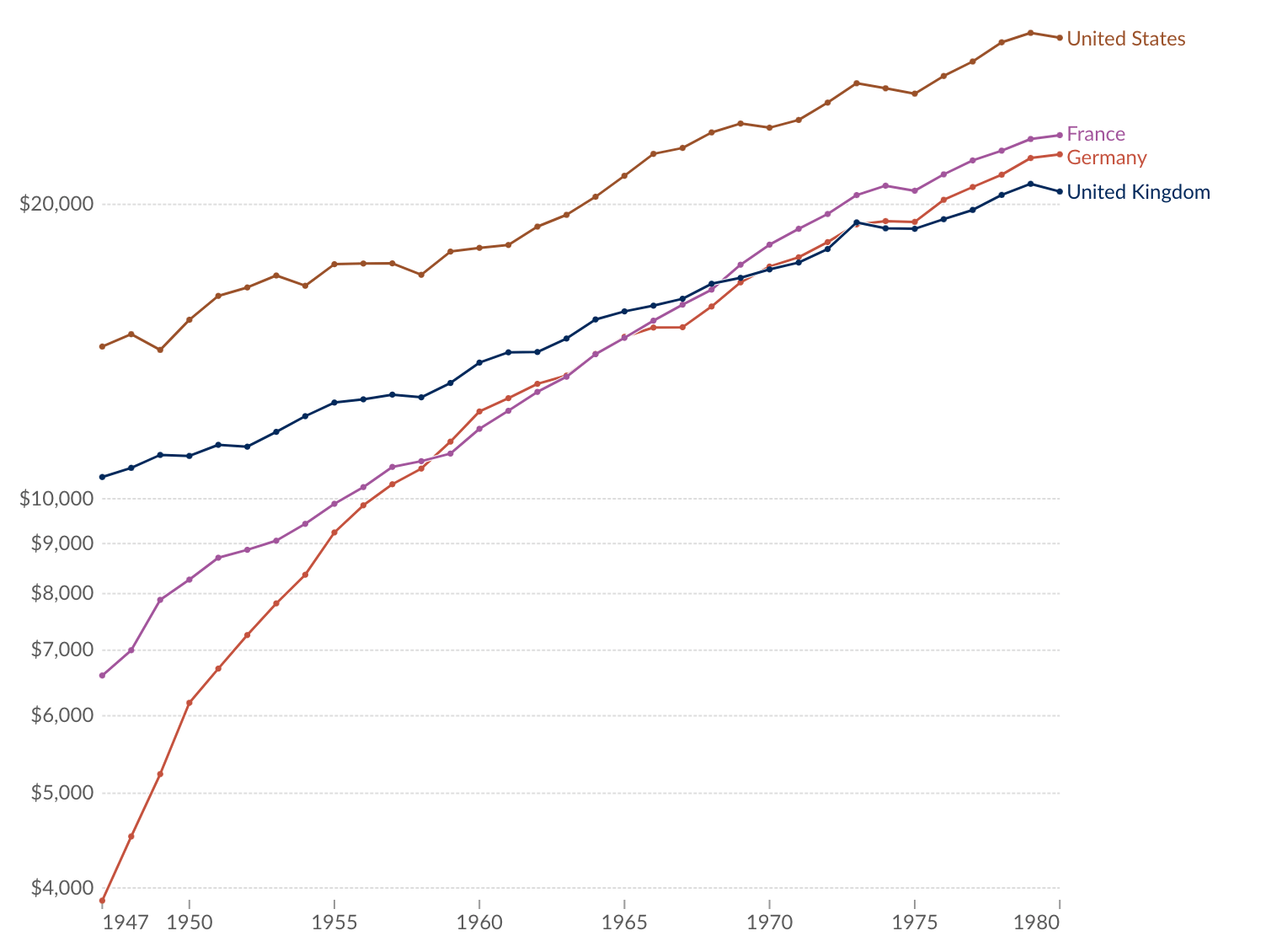

Output per capita, current prices, 1947-1980. Britain entered the

postwar era with a huge advantage over Europe, which it rapidly

lost, falling behind both France and Germany

Output per capita, current prices, 1947-1980. Britain entered the

postwar era with a huge advantage over Europe, which it rapidly

lost, falling behind both France and Germany

Privatisation, tax cuts, and the curbing of union power fixed important swathes of the UK economy. Crucially, they tackled chronic underinvestment in sectors that had been neglected under state ownership. Political incentives under state ownership encouraged underfunding – and where the Treasury did put money in, it tended to go on operational expenditures (e.g., unionised workers’ wages rather than capital investments). This problem has immediately reemerged as the Department for Transport has begun to nationalise various franchises (which it promises to do to all of them).

Between 1980 and 2008 Britain returned to its position as one of Europe’s most successful large economies. For the most part, Tony Blair’s governments were able to sustain these advances. In 2005 Britain’s GDP per capita was just 2.8 percent behind Germany’s, in purchasing power parity terms, and fully 20 percent higher in US dollar terms, according to the World Bank. Penn World Tables, the other major source, have the UK overtaking Germany on GDP per capita in the mid-2000s.

Britain’s relative success during this period is clearest when compared to other major economies. The chart below shows GDP per capita in France, Germany, Italy and the UK as a percentage of US GDP per capita. It shows Britain, after decades of relative stagnation, beginning to converge on the United States and overtake the other European countries from the early 1980s. Britain’s change of fortunes under Thatcher, and continued improvement under Blair, is clear.

But crucial parts of the economy were still left unfixed – notably land-use planning policy, which Thatcher’s Environment Secretary Nicholas Ridley had tried and failed to reform, and which Tony Blair’s government was unable to make a dent in either.

This left Britain with latent weaknesses that have become hugely problematic over the last quarter of a century. Since the 1990s, Britain has experienced rapid population growth, after decades of demographic stability, and big shifts in prosperity from some parts of the country to others. The decision to transition away from fossil fuels has created the need for huge quantities of new energy infrastructure, recently exacerbated by the war in Ukraine, but by no means beginning then. Across the developed world, great metropolitan agglomerations have become even more economically important. London has been among the biggest winners from this trend, in spite of the obstacles in its way.

What Britain needed in the last 25 years above all was a huge amount of building – of homes, energy supply, and transport infrastructure. Without it, Britain has fallen behind, weighed down by a development system that worked badly even in the 1950s and 60s, and that is positively disastrous today.

That gap continues to grow. Between 2010 and 2019, worker productivity grew by eight percent in the United States, 9.6 percent in France and just 5.8 percent in Britain. And those countries’ growth rates pale in comparison to that of Poland, which has grown its productivity by 29.7 percent between 2010 and 2019, and on current trends will overtake Britain by the end of this decade.

To put the shortfall since 2008 into perspective, if Britain had grown in line with its trend between 1979 and 2008, it would be 24.8 percent more productive today. Assuming we continued working the same hours annually, that would mean a GDP per capita of £41,800 instead of £33,500, making the typical family about £8,700 better off before taxes and transfers. Tax revenues would be £1,282 billion instead of £1,027 billion, assuming tax rates are held constant. That would mean that, instead of a deficit of £85 billion, on current spending we would have a surplus of £170 billion, meaning that taxes could be much lower, and public services could be better funded.

Though these figures may seem improbably high, they are not out of line with the world’s richest economies, and there is no reason Britain should not aim to sit among them as it once did. This essay argues that Britain can do so by adopting a programme of reform similar in its scale of ambition to that of the programme of liberalisation in the 1980s. Where earlier reforms were focused on cutting taxes, curbing the power of the trade unions, and privatising state-run industries, this time we must focus on making it easier to invest in homes, labs, railways, roads, bridges, interconnectors, and nuclear reactors.

The importance of strong foundations

Why is France so rich?

France is notoriously heavily regulated and dominated by labour unions. In 2023, the country was brought to a standstill by strikes against proposals to raise the age of retirement from 62 to 64. French workers have been known to strike by kidnapping their chief executives – a practice that the public there reportedly supports – and strikes are so common that French unions have designed special barbecues that fit in tram tracks so they can grill sausages while they march.

France is notoriously heavily taxed. Factoring in employer-side taxes in addition to those the employee actually sees, a French company would have to spend €137,822 on wages and employer-side taxes for a worker to earn a nominal salary of €100,000, from which they would take home €61,041. For a British worker to take home the same amount after tax (£52,715, equivalent to €61,041), a British employer would only have to spend €97,765.33 (£84,435.6) on wages and employer-side taxes.

And yet, despite these high taxes, onerous regulations, and powerful unions, French workers are significantly more productive than British ones – closer to Americans than to us. France’s GDP per capita is only about the same as the UK’s because French workers take more time off on holiday and work shorter hours.

What can explain France’s prosperity in spite of its high taxes and high business regulations? France can afford such a large, interventionist state because it does a good job building the things that Britain blocks: housing, infrastructure and energy supply.

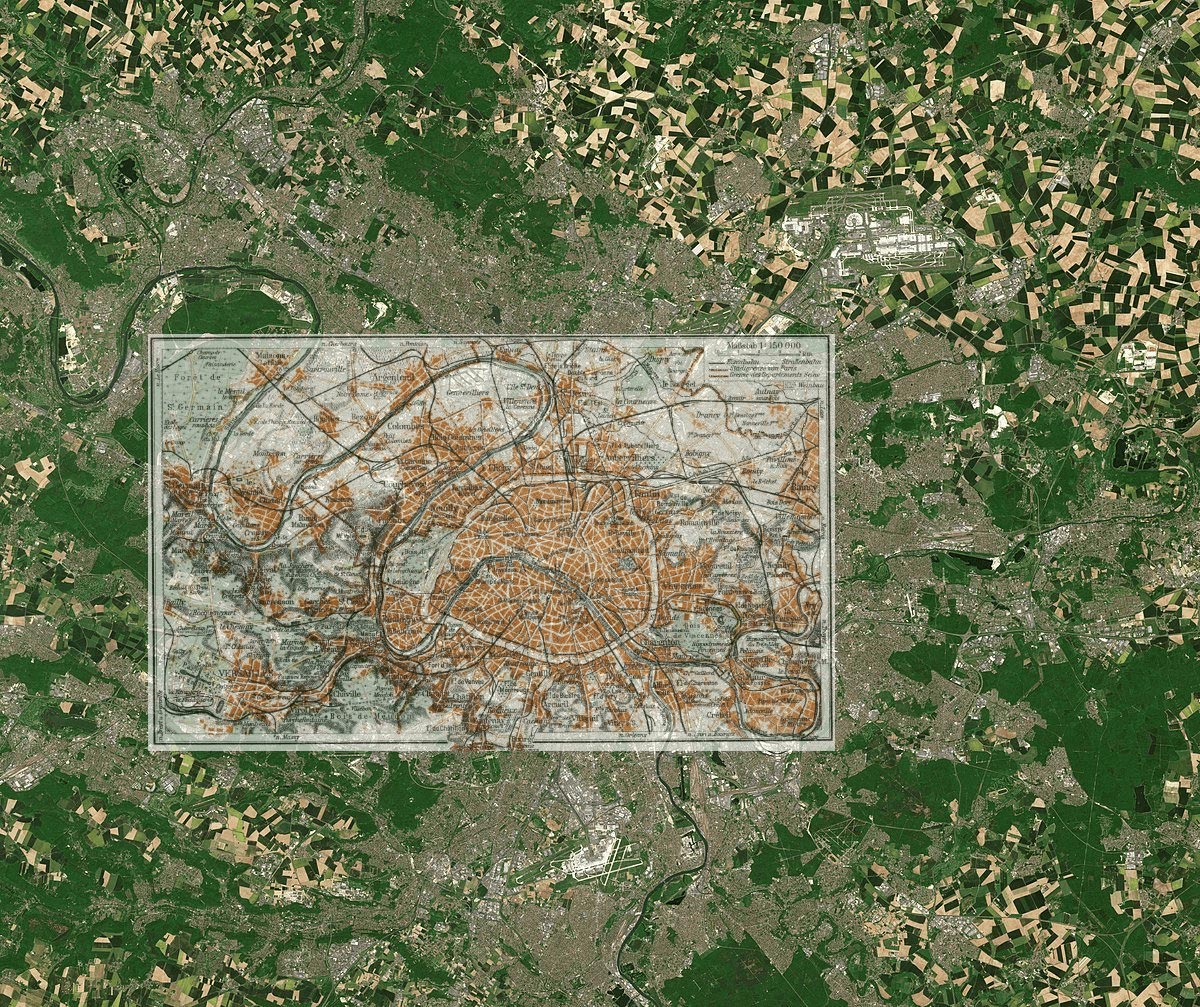

Housing supply is vastly freer in France. Overall, it now has about seven million more homes than Britain (37 million versus 30 million), with the same number of people. Those homes are newer, and are more concentrated in the places people want to live: its prosperous cities and holiday regions. The overall geographic extent of Paris’s metropolitan area roughly tripled between 1945 and today, whereas London’s has grown only a few percent. France has allowed its other great cities to grow and flourish too, whereas Britain has systematically constrained and undermined them for seven decades.

Paris, 1937 and today: the 1937 map is inset in the contemporary

one. Everything outside the centre is still new. London is almost

unchanged in surface area today from 1937.

Paris, 1937 and today: the 1937 map is inset in the contemporary

one. Everything outside the centre is still new. London is almost

unchanged in surface area today from 1937.

Transport infrastructure is now better there: there are seven British tram networks, versus 29 in France. Six French cities have underground metro systems, against three in Britain. Since 1980, France has opened 1,740 miles of high speed rail, compared to just 67 miles in Britain. France has nearly 12,000 kilometres of motorways versus around 4,000 kilometres here – and French motorways tend to be smoother and better kept (and three quarters are tolled, making congestion much less of a problem). In the last 25 years alone, the French built more miles of motorway than the entire UK motorway network. They are even allowed to drive around 10 miles per hour faster on them.

Energy is more abundant and, thanks to the country’s nuclear roll-out from the 1970s, the country has already done a lot of decarbonisation. Seventy percent of the country’s electricity comes from nuclear power, which does not suffer from the intermittency problems that wind and solar power both face, which drive up their costs significantly since they require energy storage and backup fossil fuel generation.

Britain was the first country to split the atom, and built the world’s first commercial nuclear power plant that supplied energy to a national grid, opened by the late Queen in 1956. In the following decade, Britain built ten more nuclear power stations. In 1965, we had more operational nuclear reactors than the USA, the USSR, and every other country in the world put together, yet we haven’t finished a new nuclear power station in almost three decades.

Because France gets these big things right, it can afford to get a lot of other things wrong. If Britain could catch up with France on housing, infrastructure and energy, without making the sort of mistakes it makes on regulation and tax, the implication is that we could be far richer than they are, as we were for centuries before the 1950s.

Weak foundations: investment, housing, infrastructure and energy

Britain gets many of the important things for prosperity right. Businesses from around the world come here to draw on our legal regime, low levels of corruption, centuries-old commitment to free trade, efficient financial sector, and world-leading scientific research ecosystem. Our time zone allows us to talk to Asia, Africa, and the Americas all in one day, and everyone here is fluent in the modern world’s lingua franca. As the economist Tyler Cowen said, England remains ‘one of the few places where you can really birth and execute a new idea’. This is unbelievably precious, rare, and difficult to create.

But we fail to capitalise on these rare advantages because the economy lacks the most important foundations: private investment is blocked from going where it could generate the highest returns, meaning we have lower investment than all our peer economies; in particular we do not allow investment in the infrastructure we need to allow people to access prosperous areas, the houses they need to live there, and the offices, labs, factories, and warehouses they need to work there, which, together with our high and rising energy costs, stop the companies in those cities reaching their full potential.

Britain’s best chance of achieving rapid economic growth in the near term is via a combination of higher private investment, more agglomeration – that is, greater clustering of economic activity in productive places – and lower energy costs.

These economic foundations are important determinants of how productive workers and businesses are.

No individual by themselves can create much value, no matter how gifted or hardworking they might be. They need to combine their efforts with machinery and other people to really succeed. Investment rates determine the amount and quality of the tools they can use; energy costs determine how they can use them; and agglomeration – including both housing and infrastructure – determines who they can use them with.

Output per capita, current prices, 1990-2022. Those middle-income countries that have decent institutions have been rapidly converging on Britain

These policies are a complement to Britain’s most advanced frontier sectors. More agglomeration drives higher rates of innovation, and increases the choices that businesses have about who to hire. Lower energy costs make certain high-tech sectors more viable, such as advanced manufacturing and AI training. Higher rates of investment into businesses make it easier for smaller companies to rapidly scale up into giants.

Rapid economic growth is possible for Britain. Because what we get wrong is so mundane and straightforward, fixing these problems would allow Britain to experience similar rapid ‘catch-up’ growth that countries like South Korea, Estonia, and Poland have experienced over the past thirty years.

Investment

Investment is when we forgo resources that we would consume today, and instead use them to produce more resources in the future. It is the life-blood of economic growth, and of individual businesses’ successes. Investment is not just what happens after we build sufficient roads, houses, pylons, and power plants: building those things is investment.

What is good about building these things is not that they cost money, and what matters is not how much money we spend on investment. It is the things we actually produce, and the benefits they give us, that are valuable: the easier and less expensive it is to build them, the higher the return we get for a given amount of money invested, and the better it is to spend money on them.

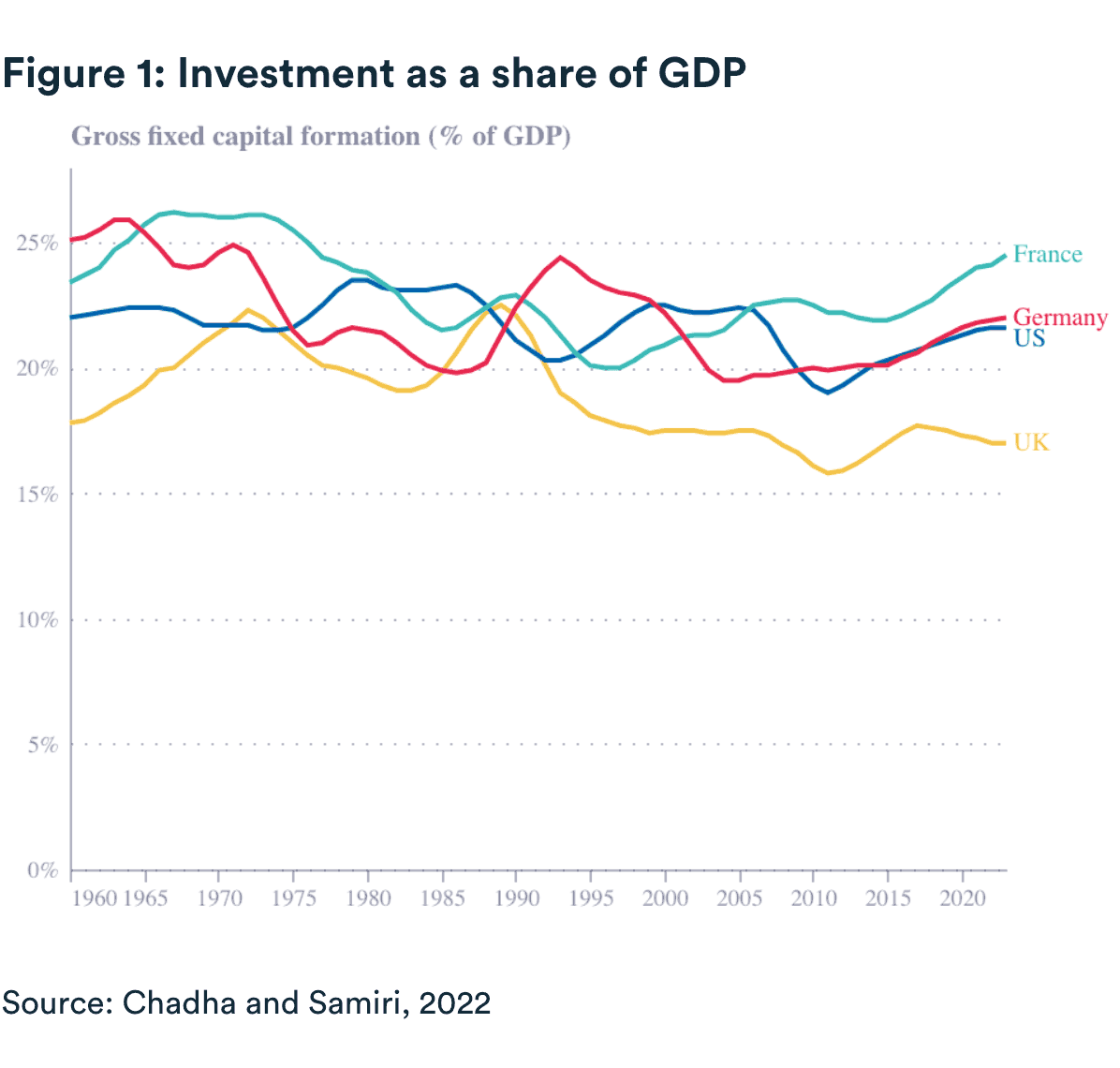

Britain does invest at a lower rate than most other advanced countries. In 2022, France spent (across both public bodies and private companies) 26 percent of its GDP on physical capital investment; Germany 25 percent; OECD members 23 percent on average; the United Kingdom just 19 percent. The total capital stock of the UK is actually lower now than it was in 2016; by comparison, it is 14 percent higher on average across the rest of the G7.

The most important reason for this is not that we are inherently penny-pinching and short-termist, where Americans and Europeans are not. It is that we have banned most of the most productive investments we could make, made it eye-wateringly expensive to do the ones we do allow ourselves to make, and allowed many publicly-managed assets to be neglected.

These problems have been present for more than half a century. In the postwar decades, the British state chronically failed to invest in the various companies it had nationalised, succumbing to the permanent temptation of politicians to allocate resources to frontline services (i.e. immediate consumption) rather than investing for the long term. We see this every year with the NHS, whose operational budget continues to rise, but which has the fewest MRI and CT scanners of any developed country’s healthcare system, and by far the least machinery and equipment overall.

British Rail ran in 1994 a third as many trains between London and Manchester as did private franchises by the 2010s – overall passenger numbers fell steadily between nationalisation in 1948 and privatisation in 1994, after which point they have more than doubled. Many state-run British industries became efficient in terms of economising on the scarce resources they were allowed, but extremely inefficient in terms of overall productivity.

The privatisations of British Steel, British Airways, British Gas, British Telecoms and many other nationalised companies in the 1980s and 90s thus opened up great opportunities. From 1981 to 1990, British capital investment grew faster than any other country in the OECD barring booming Japan and tiny Luxembourg. Contrary to what is sometimes claimed, North Sea oil and gas was not the biggest part of this, with investment in it actually falling over this period. Investment levels rose chiefly because state mismanagement had left so many opportunities untaken in the preceding decades – opportunities that privatisation opened up.

Underinvestment leads to particularly acute problems in places like the North of England that have historically prospered from capital-intensive industries. These areas have the same underlying features that generate industrial heartlands elsewhere, like in Germany and Sweden: relatively cheap land, proximity to waterways, roads and rail networks, and – unlike many other parts of Britain – cheap, abundant housing. But expensive energy and the difficulty of building new premises, warehouses, factories, pipelines, pylons, distribution centres, and so on holds them back.

Some of this underinvestment is due to distortions in the tax code that penalise capital investments. Prior to the introduction of full expensing, British businesses that invested in machinery, buildings and acquired patents could only claim back 62 percent of the costs from their corporation tax bill (compared to 100 percent for operating expenses like rent or wages), which meant that despite the UK having a low headline rate of corporation tax, the effective rate on profits generated via physical investments was still high. The introduction of full expensing has corrected this for some investments, but still does not apply to buildings or machinery with an expected lifespan of over twenty-five years. Business rates, meanwhile, have the effect of increasing the tax liability when most property enhancements are made, regardless of when or if they become profitable.

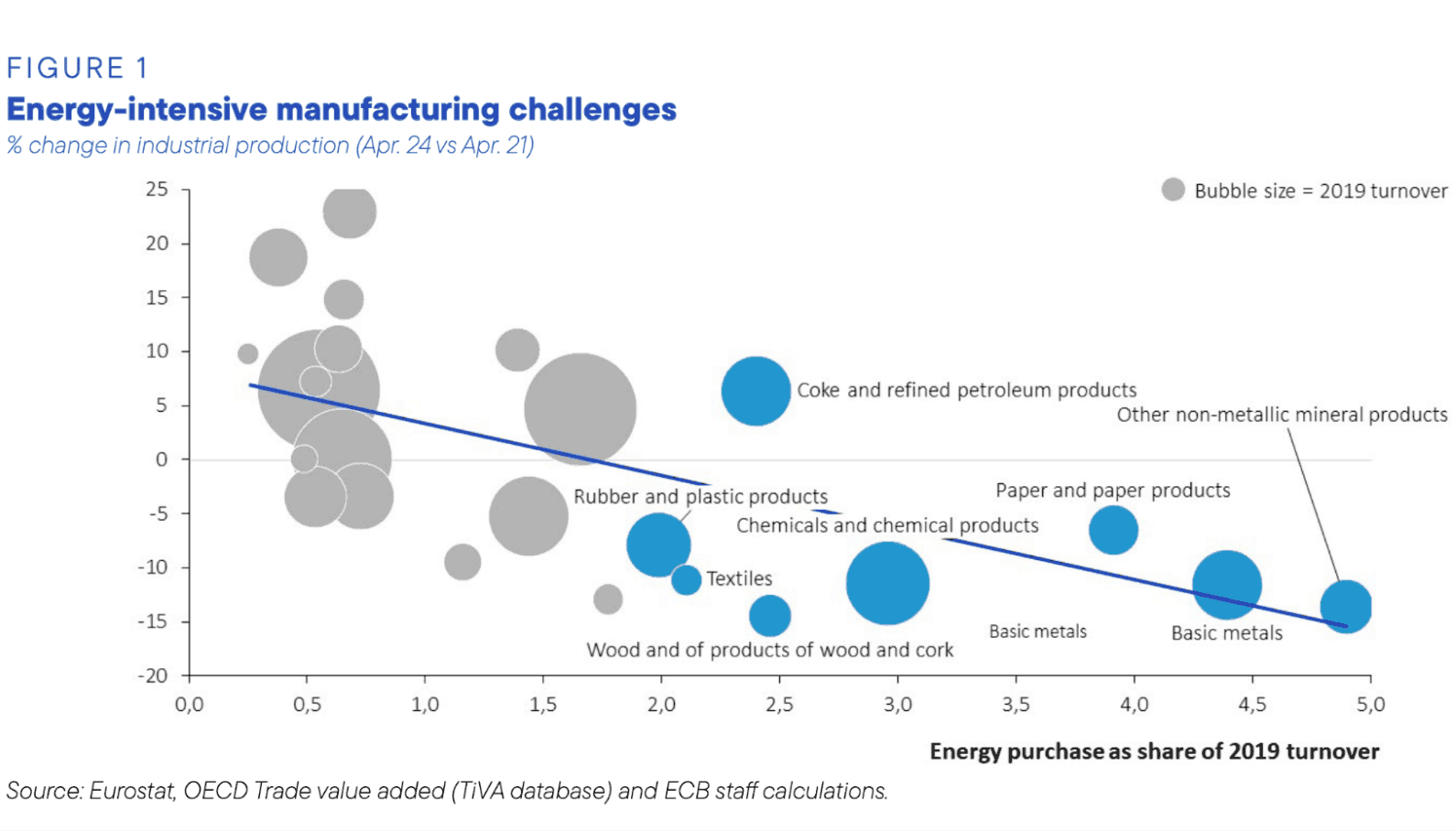

Some of the underinvestment is due to higher input costs, such as the high cost of energy, discussed later. This is most acutely a problem for the manufacturing sector, where high energy costs have made many industries unviable in Britain, while they thrive in other advanced economies.

But the most important reason Britain sees underinvestment today is that the state bans the very investments that would be most valuable. If allowed, private investors would be rushing to build housing, transport infrastructure and energy infrastructure. France’s thousands of miles of motorways were built, and are operated by, private companies. Britain’s roads, canals, and railways were originally built this way. If done today, this would show up as enormous amounts of capital investment in the national accounts. But as we will show, building these things is prohibited in the vast majority of cases in which it would be economically rational. If we change that, Britain would see an enormous construction boom as suppressed demand for these things was met, and the resulting capital assets would continue contributing to the economy indefinitely.

Improving the UK’s investment rate would bring great benefits: about half the shortfall in productivity growth since the financial crisis can be attributed to underinvestment in (tangible) capital, while much of the rest is likely to be due to the shortfall in intangible investments like R&D.

Investment is what makes us richer over time. Any successful economic plan will have to unleash it in order to succeed. But even as the need for higher investment becomes more widely accepted by Britain’s economic commentators, they tend to propose more quangos and subsidies to tackle the problem, because they miss two crucial points.

First: private investment is far more significant than government investment. Public investment can be extremely important, especially in areas that have large spillovers to the broad economy, but which do not always generate a private return. But more than 80 percent of investment in the UK and most other developed countries is done by the private sector. Public investment was 18.0 percent of the UK total in 2021, 17.6 percent in 2020, and 15.5 percent in 2019.

And second: apart from taxes on investment like corporation tax and capital gains tax, higher investment in the UK is mainly frustrated by systems that effectively ban private companies from doing it (like building houses, infrastructure, and energy generation), rather than being down to short-sightedness by these businesses, or a lack of generosity by government.

Commentators have searched far and wide for explanations of Britain’s investment problem. But the explanation was before our eyes all along. Buildings, energy and transport infrastructure are the investments that Britain most needs, and they are largely banned. In banning them, we have generated higher costs for a range of other investments too. There is no need to posit esoteric cultural problems among British businesspeople, no need for a dozen more government strategies, deals and consultations. We don’t need to pay businesses to invest more. We just need to stop banning them from doing so.

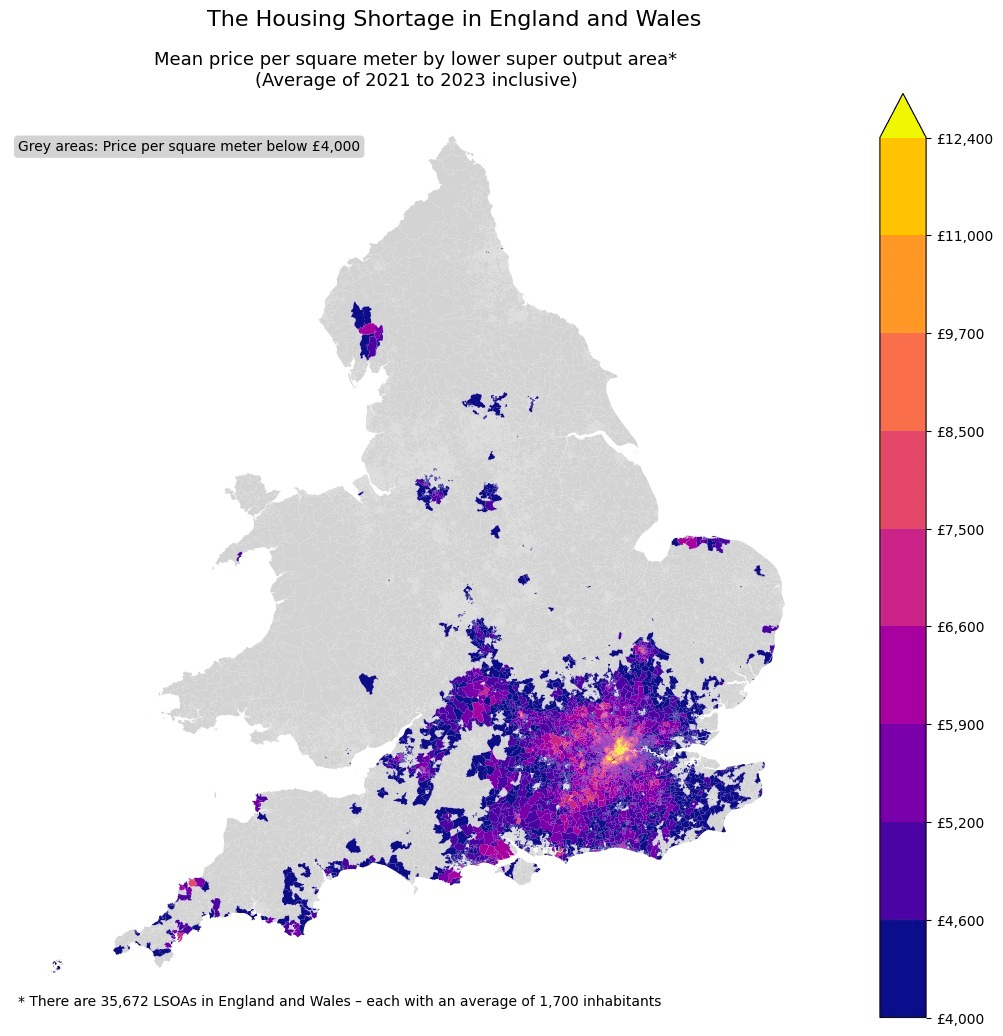

Housing

Why we’re not building enough homes in the right places

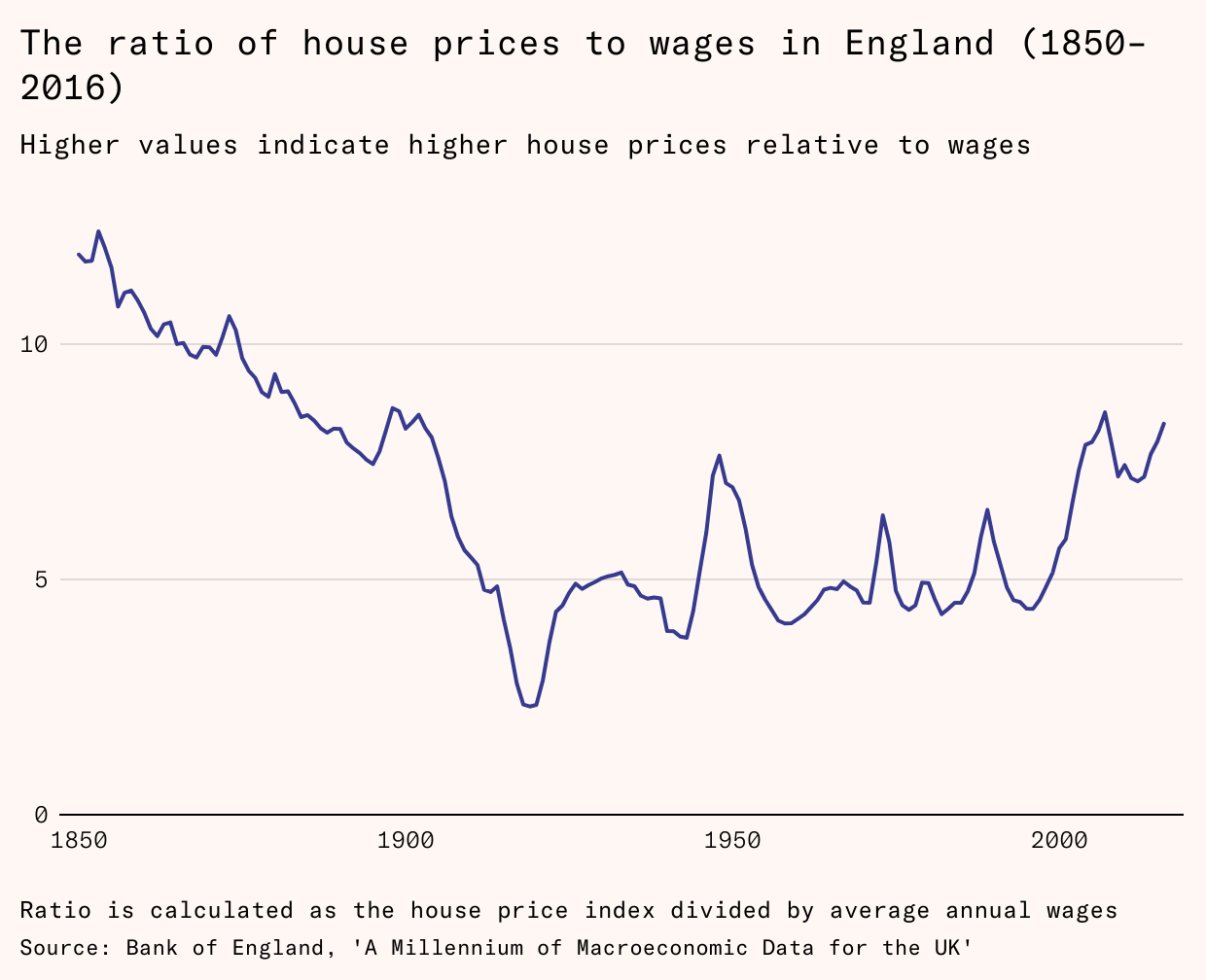

For centuries, Britain had a development control system that supported urban growth in the places with the most successful industries, as well as building beautiful cities that we treasure today. Since 1947, however, Britain has had probably the most restrictive development control system in the world. This has held back our strongest sectors and businesses and stopped people from moving to the places with the best jobs. On its own, we see it as the largest cause of British stagnation.

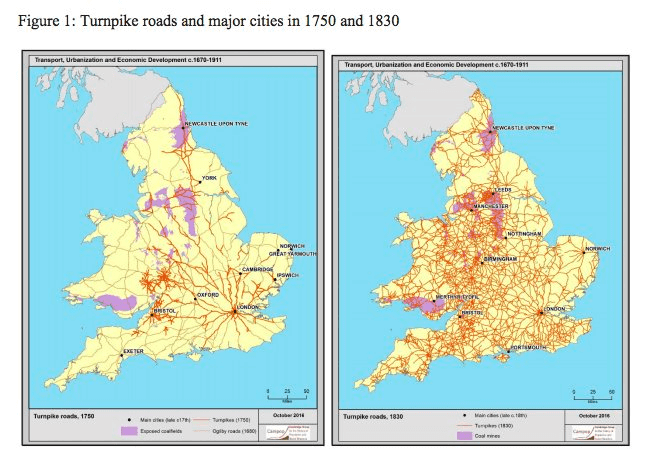

Throughout Britain’s history, its economic centre of gravity has changed, sometimes profoundly. During the 1800s, millions of people migrated to the cities of the Midlands, Wales, and especially the North of England, where the Industrial Revolution was revolutionising the world economy. Cardiff grew by around 1,000 percent in 45 years as people moved near the coal that enabled heavy industry. Manchester grew from 90,000 in 1800 to 700,000 in 1900, in part due to the soft water that enabled Lancashire’s world-beating cotton textiles. Liverpool grew by over 1,000 percent between 1800 and the 1930s.

This process continued in the 1930s, but as different industries came to the fore, different locations were predominant. Cities like Birmingham, Coventry, London, Leicester, and Nottingham expanded at breakneck pace as the link with raw materials was broken, and jobs shifted to offices and factories in the South and Midlands. Immense suburbs sprang up, with their characteristic long gardens and semi-detached houses. Private companies and local councils laid out a vast system of commuter rail, electric trams and motorbuses that enabled and served these new neighbourhoods. The English housing stock nearly doubled in twenty years, transforming the living standards of the English people.

As late as the 1930s, there were almost no restrictions on development, other than generous height limits in some cities (about ten storeys) and some building safety regulations. Subject to those, any property owner could build virtually anything they wanted. After 1909, developers did have to get permission to develop, but councils almost always gave it, since they had to compensate landowners for the lost value if they rejected permissions, and councils were themselves generously compensated through local property taxes if they accepted development.

In sum, before the 1940s, British cities grew as their industries did. People moved, in their millions, around the country. People moved to places where wages were higher, raising wage competition for workers in the places that they left. This meant that there were fewer and narrower persistent income differences between places than those we see today. Liberal development policy generated a country with a natural force pushing against persistent, entrenched regional inequality, which was narrowing in the decades to the 1940s and has been widening since.

The source of the problem

In 1947, the Town and Country Planning Act (TCPA) was introduced, part of the postwar reform programme that nationalised nearly every major industry, from steel to man-with-van road haulage companies, and normalised top tax rates at over 90 percent. The TCPA completely removed most of the incentive for councils to give planning permissions by removing their obligation to compensate those whose development rights they restricted. Other reforms at around the same time also redistributed away much of the upside that councils had received from development through local property taxes.

The law also added a requirement to get permission from national government for any development, and to pay to the national government a tax of 100 percent on any value that resulted from permission being granted. Most notoriously, the TCPA instituted the legal powers that were used to create and expand green belts the following decade, prohibiting development on large rings of land around England’s cities.1

Overall, it moved Britain from a system where almost any development was permitted anywhere, to one where development was nearly always prohibited. Despite some minor later liberalisations, like the introduction of permitted development rights in the 1980s, the underlying problem remains. Since the TCPA was introduced in 1947, private housebuilding has never reached Victorian levels, let alone the record progress achieved just before the Second World War.

Today, local authorities still have robust powers to reject new developments, and little incentive to accept them. Historically, local governments encouraged development because their tax bases grew in line with the extra value created, but this incentive has been eroded by successive reforms that have centralised and capped local governments’ tax-raising powers.

National governments have not been blind to the fact that development is not happening. Their solution to the problem has generally been to try to force local governments to permit the homes the country needs (and take the political flak that engenders) through targets and punishments. But this system has never managed to raise building rates by anywhere near enough to return prices to the downward trend they were on for hundreds of years until 1938.

Attempting to force local governments to build more homes has repeatedly backfired, and where it has delivered new homes they have often been low quality and far from where the highest demand for homes is, since the targets are calculated with almost no reference to actual demand for new houses. There is little reason to think the new government’s plans will be very different, and its decision to lower London’s target as a ‘reward’ for failing to meet its previous targets is a sign that it, too, will fail to build homes where they are needed most.

Local people bear many of the costs of new development – disruption, congestion, and competition over access to state-provided services like healthcare and education. At the same time, they gain few or none of the benefits, the obvious exception being those local landowners who actually receive the planning permissions. It is thus unsurprising that local people tend to be fierce opponents of development. When the national government has tried to take away their right to control development nearby, they have resisted vigorously, usually succeeding in having the targets revoked or watered down.

This has contributed to a climate that is supportive of continual increases in regulations at the national level, which add process and cost to development. Recently, this has meant compulsory second staircase requirements, which ban apartment blocks with only one staircase and lift core – the standard type in nearly every country in the developed world. (The Government’s own impact assessment of the second staircase rules determined that their costs would be more than two hundred times greater than their benefits.) It has also meant reducing the sizes of windows: it is now legally difficult to build windows as large as those common in Georgian and Victorian buildings, apparently because they cause overheating in hot weather, and because people might supposedly fall out of them.

The same climate has facilitated rules requiring every development to prove ‘nutrient neutrality’, to survey for protected species like newts and bats (even in places where their presence has never been detected), and more.

High housing costs also create the demand for destructive policies that appear to alleviate the proximate problems of expensive housing without dealing with the underlying issue. In many cases today, as many of 40 percent of a new development’s homes must be subsidised for ‘affordable’ renters instead of being made available at market rates. These requirements function as a tax on new housing (and so local objectors often support them), redistributing income from every other private tenant to a lucky few. Countries with expensive rental housing also see movements for rent controls, and punitive rental regulations, like giving every tenant the permanent right to live in the property they occupy.

The economic effects of housing shortages

Since the introduction of the British planning system in 1947, there has been very little increase in housing supply when better jobs make an area more desirable. Instead of extra homes being built, workers competing for scarce housing are forced to bid up the price of existing homes. This means that many of the income gains go to existing landlords and landowners, and that many people cannot move to better jobs at all.

Because only the best paid people can afford to move to the most prosperous cities, there is no longer general migration across the economic spectrum, as there was in the nineteenth century when it was the poorest people who were most likely to move to find better work. Today, this has created a situation where only the most gifted and educated people can afford to move to richer cities and stay there. Their less well-off peers are quite literally ‘left behind’, and compete with one another over a narrow pool of jobs, driving the wages down even further, making those places feel even more deprived.

On the other hand, social housing anchors many people to extremely central, high-value areas in our major cities. A staggering amount of central London’s housing is socially rented: 40.2 percent of Islington households are on subsidised social rents; as are 33.7 percent of Camden’s; 35.9 percent of those in Tower Hamlets; and 39.7 percent of Southwark’s. These households occupy some of the most valuable space in the country, and are trapped in their tenancies, remaining even when their homes, often damp, poorly insulated, and altogether dilapidated, are no longer fit for their changing circumstances, because they will likely end up in a less valuable, less centrally-located property if they try to move.

The result is a ‘missing middle’ in cities like London, where only the very well-off and very badly-off can afford to live there, excluding lower- and middle-income people from elsewhere in the country. Even many higher earners cannot afford to live anywhere near the centre once they have children. The impoverishment of coastal and post-industrial towns cannot be understood without looking at housing shortages in more prosperous parts of the country: both are the products of Britain’s planning system.

Since the supply of homes in successful cities is tightly constrained, the growth of our most successful companies and sectors within those cities is constrained as well. Even the people who do get to live in high-productivity places are less productive than they could be, since their employers are less able to hire mid- and lower-skilled people to support them in the workplace. It is inconceivable that Britain could have had the Industrial Revolution if it had banned workers from moving to the coalfields of South Wales and Yorkshire and the textile factories of Lancashire. It is not an exaggeration to say that Britain could be forgoing its role in another industrial revolution today – that of artificial intelligence, biotech, and related technologies – by making the corresponding mistake.

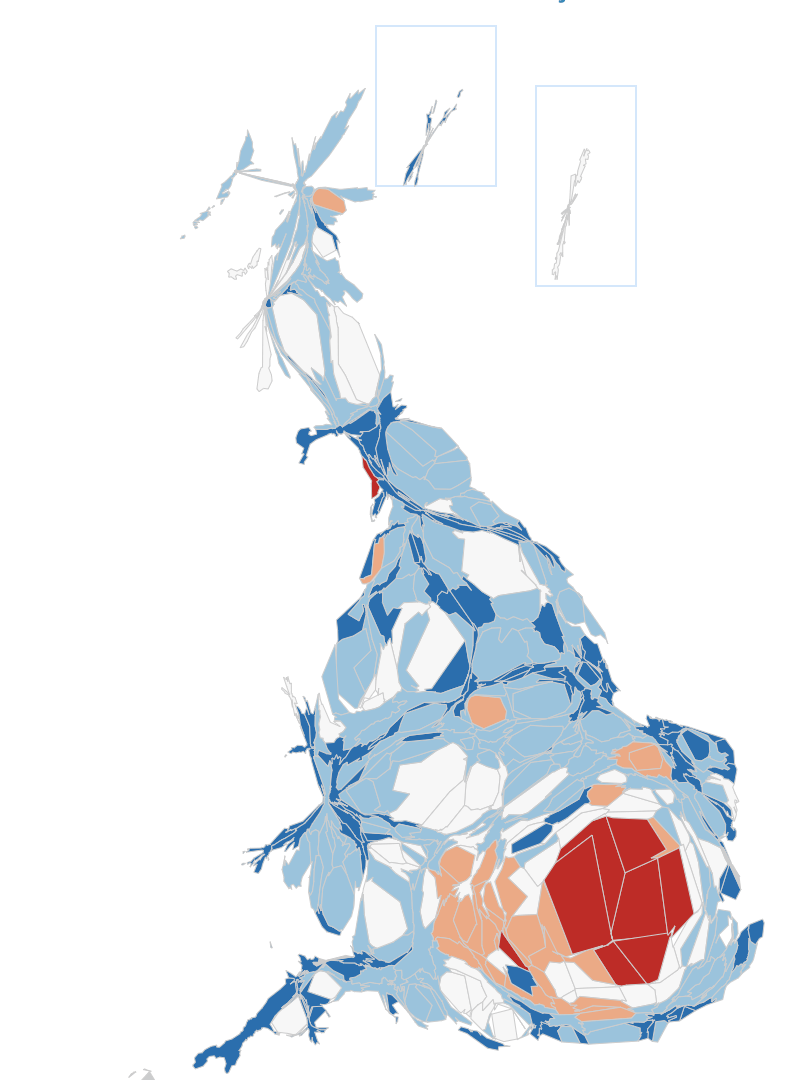

A cartogram (from the

Office for National Statistics) of the number of jobs around the country. Dark red are highest

paid, then light red, then grey, then light blue, then dark blue.

The average job in dark red areas pays about double as much as the

average job in dark blue areas.

A cartogram (from the

Office for National Statistics) of the number of jobs around the country. Dark red are highest

paid, then light red, then grey, then light blue, then dark blue.

The average job in dark red areas pays about double as much as the

average job in dark blue areas.

Britain is not the only country that has slowed its growth through holding back agglomeration. Parts of America have seen similar shortages. Economists Gilles Duranton and Diego Puga judge that if the whole of New York City allowed the densities that were common in Georgian and Victorian London, rents and house prices would fall towards construction costs, and the metropolitan area would at least double in population, to over 40 million people. Similar things would happen to the Bay Area, Boston, Los Angeles, and other US ‘superstar’ cities if higher densities were allowed. Duranton and Puga argue that huge economic growth would result from allowing these superstar cities to build more.

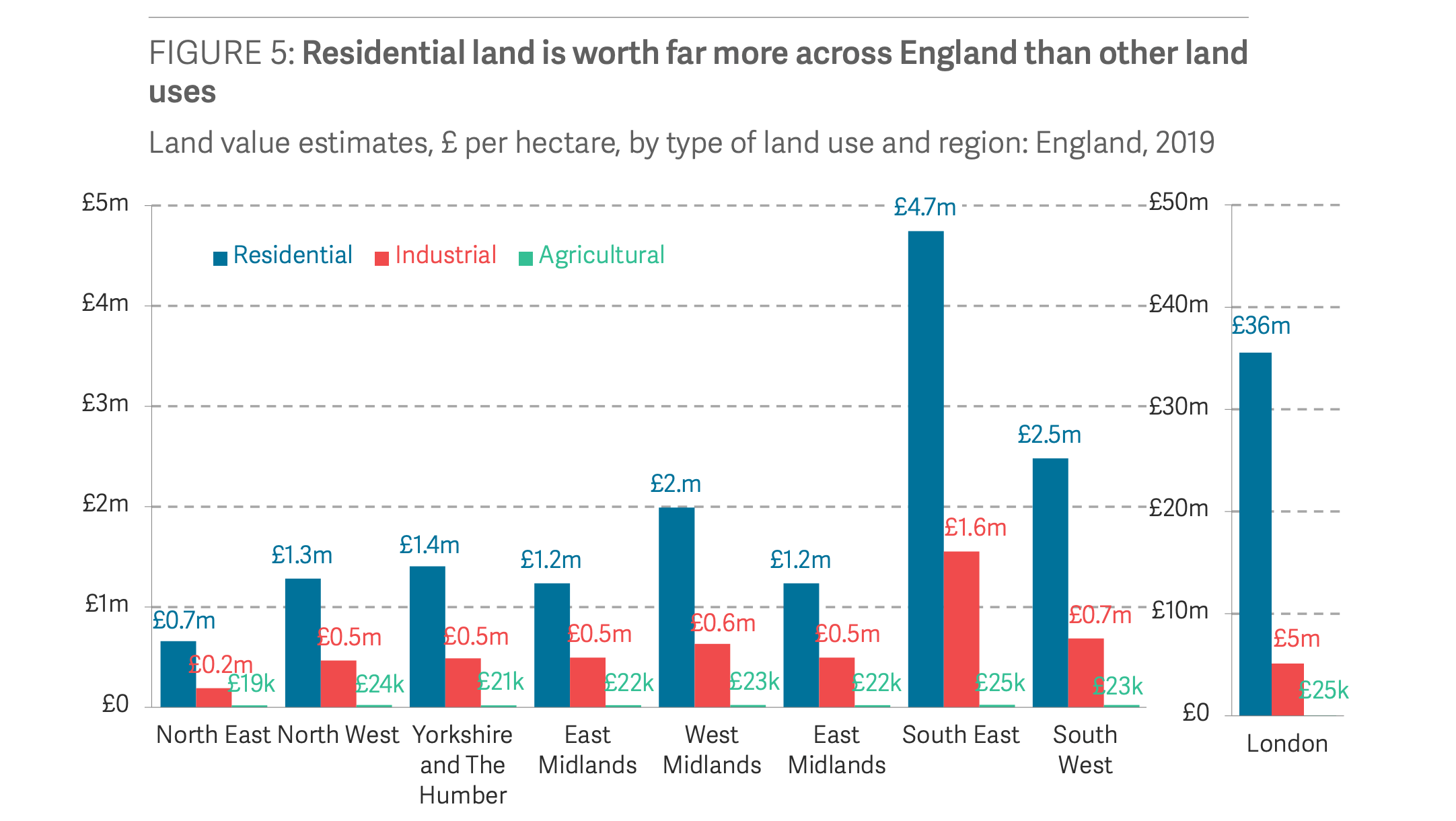

The value of land with and without planning permission. Releasing

land for development is much more valuable in some places than in

others. From

the Resolution Foundation.

The value of land with and without planning permission. Releasing

land for development is much more valuable in some places than in

others. From

the Resolution Foundation.

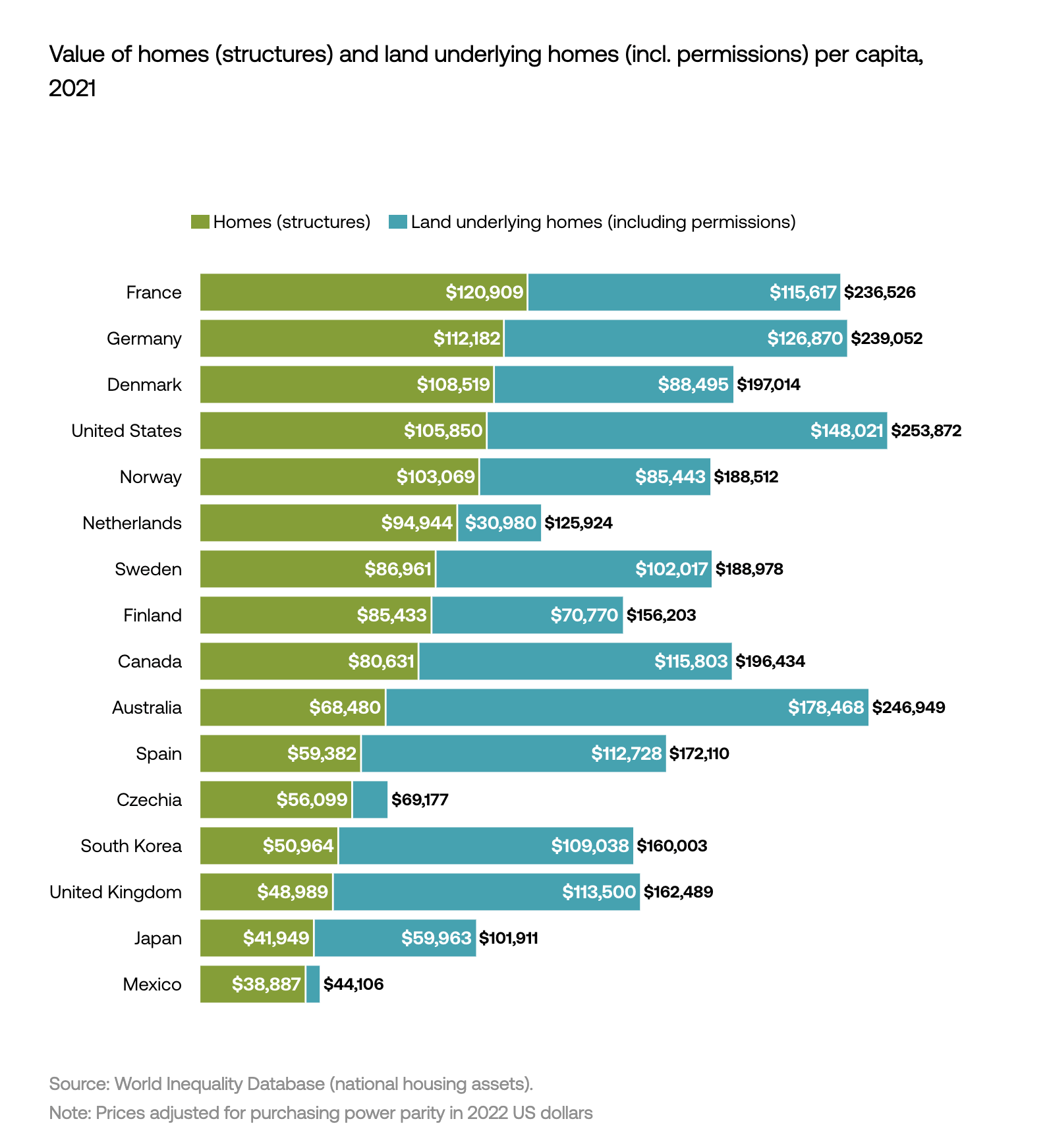

But things are much worse here in Britain. Overall, American homes only cost around a third more to buy than they do to build.2 About four fifths of American cities saw no gap at all between house prices on the edge of town and the building costs of such homes in the mid-2010s, implying no significant overall regulatory land-use barriers to development in these places.3

The UK has vastly less structure value per capita than European

competitors. (Tony Blair Institute.)

The UK has vastly less structure value per capita than European

competitors. (Tony Blair Institute.)

By contrast, the average UK house price is double the cost of building the house, and the shortage in the South East is so severe that it is spilling over to places as far away as Bristol, Peterborough, and Northampton.

Credited to

Yimby Alliance/Freddie Poser

Credited to

Yimby Alliance/Freddie Poser

The fundamental issue is that British cities are not allowed to expand upwards or outwards, whereas most American cities, like those of France, Italy and Germany, have at least been able to sprawl. Under the liberal system of the nineteenth century, late twentieth century Cambridge’s huge success in life sciences would have led to both taller buildings and many new suburbs, connected by new train lines, trams, tubes, and roads. It would likely have a population of at least a million today, just as Glasgow grew from a population of 70,000 in 1800 to over 700,000 in 1900 to facilitate its world-leading shipbuilding industry.

Today, nearly all of the potential is blocked. Scarce property means people cannot move to take up the job opportunities on offer. Some businesses never start. Others are not as productive as international competitors. Others fail to scale up to become unicorns or bigger.

Cambridge is not alone. Many of our smaller but richer cities and towns, places like Oxford or York, cannot grow up or out. The people who might have lived there, earning £600 or £700 a week, instead live in more deprived areas, earning £400. The same is true of London. It is hard to build new housing or office space, making it hard for businesses to expand, and hard for workers to move to these places to take up good jobs.

The postwar housing system has underdelivered since the 1950s: the enormous improvements in housing affordability in the Victorian and Edwardian eras stalled as soon as the new system was introduced. The problem became ever more severe each decade, even before the population began to rise rapidly: average private home sizes actually got smaller during the 1960s and 1970s. But the problem has escalated into a disaster in the last few decades, as massive net immigration, an ageing population, and unforeseen economic change have together led to huge unmet housing demand in the South. The social challenges that accompany high levels of immigration have been hugely amplified by the persistent lack of planning reform.

The same failures of the planning system apply to factories, warehouses, offices, labs, data centres, film studios, and retail centres as well. In every area where Britain has a nascent industrial advantage, we do our best to hold it back.

Britain’s strongest industries are creative and intangible, and yet we blocked a £750 million film studio by a dual carriageway, right by the UK’s strongest film cluster. Britain is the most advanced country, per capita, in artificial intelligence, but we blocked a £2.5 billion ‘super hub’ data centre site by the M25. Top talent from around the world flocks to work in biotech in Cambridge, yet we have starved the sector of lab space – under one percent of Cambridge lab space is vacant. Prime city centre office space and labs there are renting for even more than residential property.

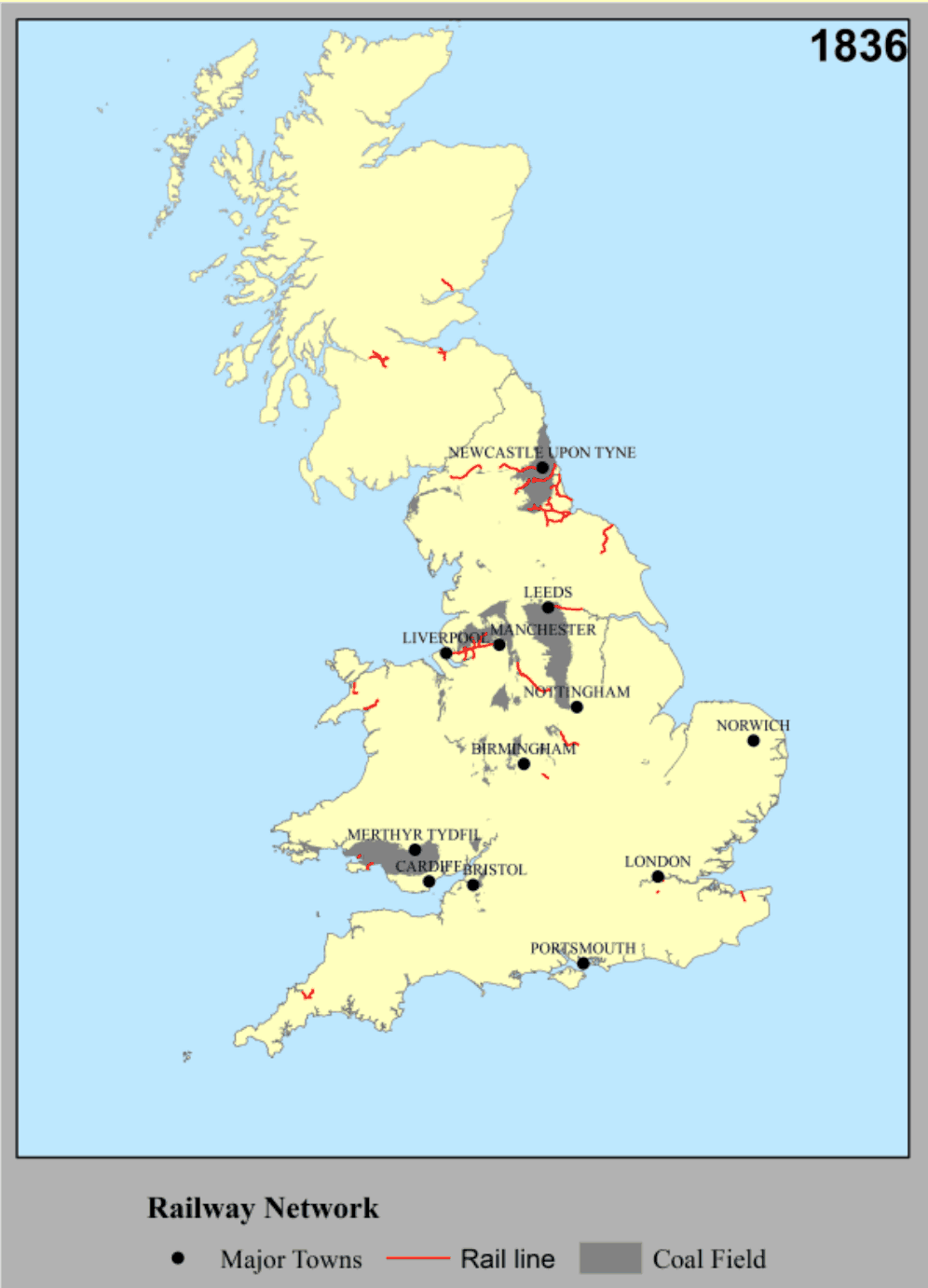

Infrastructure4

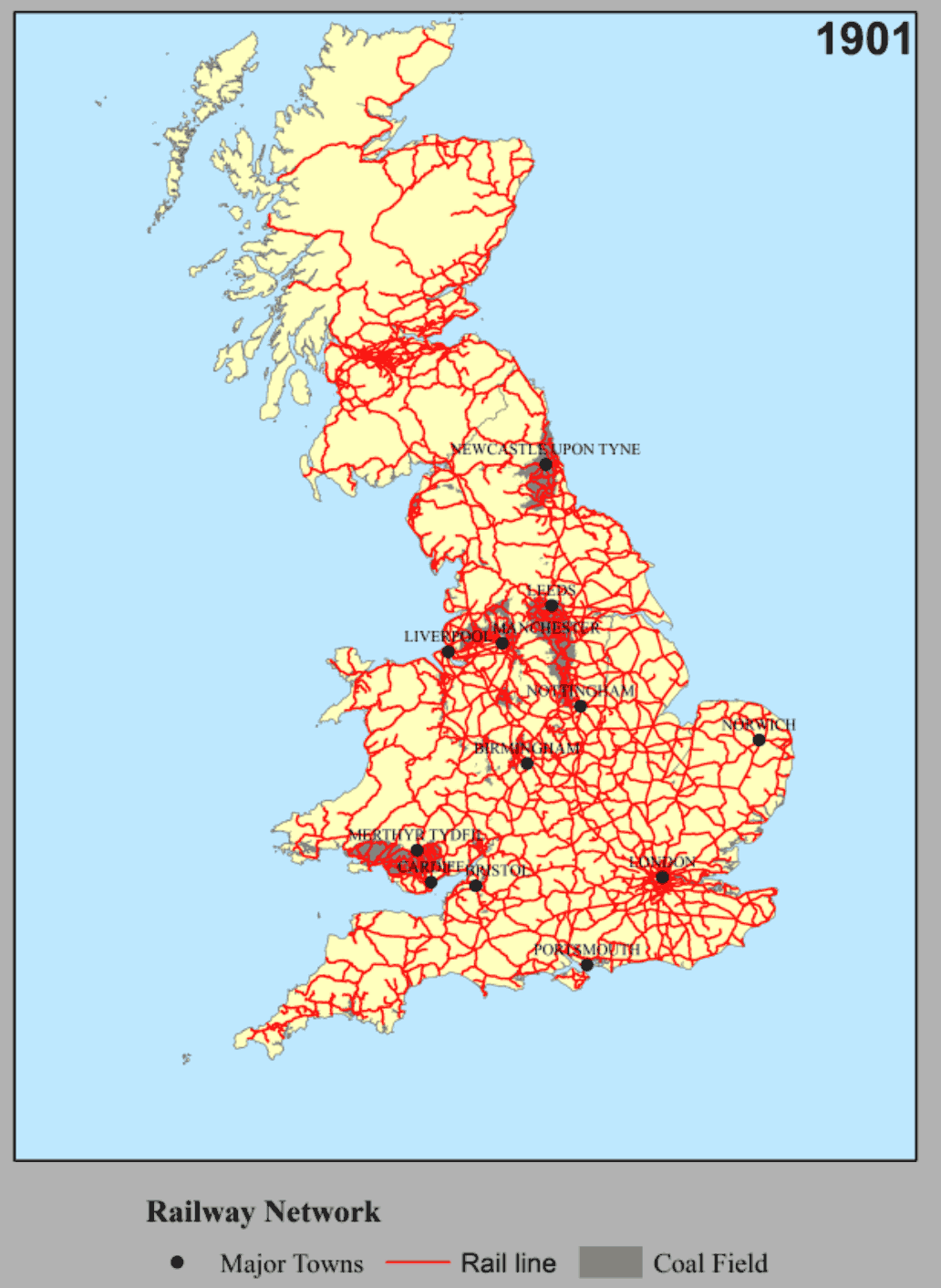

From the eighteenth to the early twentieth centuries, Britain had easily the best transport infrastructure in the world. In the eighteenth century, a total of 1,116 private companies built and renewed 22,000 miles of tolled roads, while other companies dug 4,000 miles of canals. The result was by far the best transport system in Europe. In the nineteenth century, Britain built a system of railways that is still impressive today, despite having hardly been added to since 1914 (in fact, we have half as many miles of railway today than we did then). London had an extensive underground railway system in the 1860s, almost four decades before the first underground metro line anywhere else in the world. In fact, the word ‘metro’ for underground railways comes from the Metropolitan Line, the world’s first.

In little more than a decade around 1900, private entrepreneurs built five more underground lines totalling hundreds of kilometres, still at no cost to the taxpayer. Ninety British municipalities laid electric tram networks in less than twenty years, including Europe’s longest (in London), while private companies created a gigantic fleet of motor buses. This superb transport system was one of the conditions of Britain’s revolutionary economic expansion, and of London’s position as the foremost city and unquestioned economic capital of the globe.

Although Britain’s historic infrastructure was largely delivered by the private sector (and to a lesser extent by local councils), the state did have a role. Delivering national infrastructure is extremely difficult without compulsory purchase powers: if every property owner on the route of a railway can play holdout, it is extremely unlikely to be practicable to buy them all out voluntarily. Until the 1940s, these powers were created through private Acts of Parliament: a select committee considered requests for compulsory purchase powers from the project’s promoters, and if they believed the project was in the national interest, they created an ad hoc law giving the promoters the powers they needed to make it happen. This system was extraordinarily swift and inexpensive: the planning process for major national projects generally took months.

By contrast, today’s system is broken. For a whole range of infrastructure – railways, trams, nuclear power, and more – building has become vastly more expensive than competitors across Europe and East Asia. The consenting of major projects usually takes years, and sometimes decades. A suite of reforms in 2008 seems to have produced only moderate improvements, many of which have since been lost. A key national strength has become a key national weakness.

Railways

On a per-mile basis, Britain now faces some of the highest railway costs in the world. These costs push numerous potential schemes into financial unviability – schemes that would have prospered in the past, and that would prosper in other countries today. High construction costs are effectively precluding a rail transport boom such as Britain enjoyed in the nineteenth century, or France is enjoying today.

Even if it had only cost as much as planned in 2013, HS2 would have been between two and four times more expensive than high speed rail lines in Italy and France. In fact it cost a lot more: the section we end up building will be between four and eight times more expensive per mile than French or Italian high speed rail projects.

At £18.1 billion for the tunnelled Paddington to Stratford section, the Elizabeth Line (Crossrail) was the second most expensive metro line ever built, at £1.4 billion per mile. By comparison, Madrid built a 120-mile new underground network in twelve years (with much of the network open after just four years) for £68 million per mile – twenty times cheaper than Crossrail and nine times cheaper than the Jubilee line extension built around the same time. Copenhagen built a 9.6 mile underground line in 2019 at a total cost of £3.4 billion or £350 million per mile (four times cheaper). Crossrail 2 (if it is ever built) is expected to cost even more than the Elizabeth Line did per mile.

Despite its astonishing construction cost, the Elizabeth Line is so valuable to London that it is probably still good value for money. But if construction costs were more moderate, dozens of other rail schemes would be good value for money too.

Britain has also lagged behind on electrification, one of the most important transformations in modern railway technology. Electrified railways are simply better - they allow trains to accelerate faster and reach higher speeds. Electric trains require at least five times less maintenance and suffer fewer breakdowns compared to diesel trains, driving huge gains in reliability. These lower maintenance costs, combined with the fact that expensive diesel isn’t needed to power the trains, means that electrification often saves money in the long run.

In the 1890s, electrification rapidly transformed intra-city rail transport. In London alone, the Northern, Piccadilly, Bakerloo, Central and Waterloo & City Lines were opened between 1890 and 1906, transforming urban mobility and galvanising a wave of suburban expansion. But although intercity electrification has been possible for many decades, it has been adopted painfully slowly. Just 38 percent of British railways are electrified, compared to 71 percent of railways in Italy, 61 percent in Germany, and 55 percent in France. India recently electrified hundreds of thousands of kilometres of its network in just ten years – it is now 94 percent electrified. Once more, the key constraint is cost: British per mile electrification costs are more than double those of Germany or Denmark.5

Tramways

Trams are potentially a far cheaper way of doing mass transit than underground railways. In the early twentieth century, some two hundred British towns and cities had trams: an immense network that flowered between 1890 and the 1950s, enabling urban expansion, economic growth and higher living standards.

Due to their efficiency on heavily travelled routes, many countries are now renewing and reopening tram lines. The outstanding case is France, which has built 21 tramways in recent decades. Britain has begun to make efforts to do the same, but Britain's tram projects are 2.5 times more expensive than French projects per mile, hamstringing the renaissance of the tram in this country. There are now French cities of 150,000 people with fast modern tram systems - towns comparable in size to Carlisle or Lincoln. It is inconceivable that cities of this size could get tramways in England at current build costs.

This has led to some profoundly dissatisfying outcomes. Leeds is now the largest city in Europe without a metro system: there are about 830,000 people in the official greater Leeds area, 2.3 million in the broader metropolitan area, and 2.6 million within 50 kilometres, the same as Munich. Munich has an 11.4 kilometre tunnel in the centre of the city allowing it to turn its seven commuter railways into Crossrails, plus eight underground metro lines with around 100 stations, totalling more than 100 kilometres in length.

In 1993, the John Major government granted all the necessary powers to build a Leeds ‘Supertram’. But it would have cost £1 billion (£1.6 billion in 2023 prices), on a per-mile basis twice the cost of the average French tramway. This is a key reason why it hasn’t been built in the 31 years since. It’s an especially ironic failure given that a daring private company opened Europe’s first overhead-powered tram network in Leeds in 1891 – a wildly successful project that was subsequently emulated in every major city.

Why is infrastructure so expensive in Britain?

There are a range of proximate causes for Britain’s high infrastructure costs. Some of them are unalterable: for example, Britain was the first place to install below-street utilities, so we don’t have a very good idea of the pipes hidden under our feet, and tunnelling through soft London clay can perversely be more difficult than through hard Norwegian rock. But many of the key factors have appeared during the last two to three decades, the period during which infrastructure costs have exploded.

- We gold plate designs, spending extra billions on features that don’t enhance functionality, as with the award-winning Jubilee Line stations, or the plan for HS2 to run 60 kilometres per hour faster than is typical for European high-speed rail. Older infrastructure systems like the Victoria Line, the DLR or the Croydon Tramlink made do with simple repeated station designs, which hugely reduced their cost: the same tends to be true with Continental transport infrastructure today.

- We waste money on newt and bat surveys and other environmental assessments – like the 18,000 pages, costing £32 million, on reopening just three miles of track for the Bristol-Portishead rail link. The Jubilee Line Extension’s environmental statement in the early 1990s was just 400 pages long.

- HS2 will be required to dig 105 kilometres of tunnels and cuttings between London and Birmingham to avoid disturbing landscapes, at fantastical expense to the British people.

- The UK is vulnerable to judicial review – the Aarhus Convention means that campaigners can sue projects and hold them up for years at little cost, even when they know they will lose, at a cost of billions.

- We have excessive consultations and produce excessive documents, like the 359,000 pages prepared for the Lower Thames Crossing across many rounds of consultation.

- We often redesign projects multiple times in response to successive waves of ‘stakeholder’ interventions. Successful projects manage this by empowering specialists to make engineering and design decisions on the fly. Unsuccessful projects use generalists or consultants who have to re-approve every small edit they make.

- Instead of a steady pipeline of projects, we have a ‘feast and famine’ approach. Germany electrifies roughly 200 kilometres of track every year, while Britain oscillates between electrifying 0 and up to 900. This inconsistency prevents businesses from investing in equipment and training construction workers, and stops civil servants developing expertise about efficiently running these projects.

- All these problems lead to high borrowing costs for the engineering companies contracted to deliver the projects, because of the risks they incur (e.g. two thirds of the cost of Hinkley Point C is financing the project).

Analysis of the failures of British infrastructure delivery tends to stop here. But we believe that these proximate causes largely arise from a common source, which is the excessive centralisation of funding and consenting of infrastructure in the national government that has steadily taken place since the 1990s. This has dramatically narrowed the constituency who want infrastructure projects to go ahead while also wanting to minimise their costs. The various ways in which British infrastructure projects have become increasingly slow, contested and expensive are all functions of this underlying mechanism.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, infrastructure was generally funded and delivered privately. The railway system, the canal network, the turnpike roads and the London Underground were all built by private companies.

Quasi-private models remained common to the end of the twentieth century, including ‘build, own, operate, transfer’ (the Channel Tunnel) and the private finance initiative (M6 Toll, Tramlink). Other schemes were delivered through arms-length bodies, like London Transport (Victoria Line). Others still were delivered by local governments. Most of Britain’s 300-some tram networks were laid by local authorities, with neither support nor direction from national government.

In all of these cases there is a strong constituency who both strongly want the project to go ahead, and also want costs to stay low. Private companies may literally cease to exist if they fail to deliver their product while keeping costs reasonably low, and although local governments will continue to exist in some form, local councillors will be punished severely by the small local electorates who have to pick up the bill generated by their mismanagement. Companies and financially responsible local governments thus have a vivid interest in keeping costs down if they are on the hook for them, and they will lobby zealously against cost bloating. A leading historian of Britain’s tram networks writes of the ‘ardent desire’ of local councils that tram networks turn a profit, which could then be used to subsidise other services or cut local rates. Sure enough, councils vigorously cut costs, dispensing with the expensive underground wire systems that were widely used in Continental cities as a sop to local objectors.

This pattern of behaviour continues to hold today in many countries. French cities pay 50 percent towards nearly all mass transit projects that affect them, and sometimes 100 percent (with regional and national government contributing the rest). Unsurprisingly, they then fight energetically to suppress cost bloat, and they generally succeed. The Madrid Metro, one of the world’s finest systems, was funded entirely by the Madrid region. A smaller and poorer municipality than London succeeded in financing 203 kilometres of metro extensions with 132 stations between 1995 and 2011, about 13 times the length of the contemporary Jubilee Line Extension in London. Other countries still operate systems of private infrastructure delivery: Tokyo’s legendary transit network is delivered, and regularly expanded, by private companies who fund development by speculating on land around stations. France’s superb system of motorways is built and maintained by private companies, who manage them with vigour and financial discipline.

In Britain, the centralisation of infrastructure delivery in the national government has fundamentally weakened this incentive. No public body will ever have quite the existential interest in cost control that a private one does. But national government also has a weaker interest in it than a financially responsible local government does, because the cost is diffused around a vastly larger electorate. The £300 million spent on the Lower Thames Crossing consenting process is one of the great absurdities of modern British governance, but it still comes to less than £5 per British person. For almost any given infrastructure project, the national Government can waste money buying off militant stakeholder groups, and the immediate cost remains invisibly small to the huge electorate that ultimately bears it. But the aggregate effect of all these small pay-offs is outrageous cost bloat, unaffordable infrastructure, and the relative impoverishment of the country.

Consider the Edinburgh Tram. It was built in two phases. The first, completed in 2014, was described as ‘hell on wheels’, by its former chairman, overrunning from a £545 million budget to £776 million. Of the original budget, £500 million came directly from the Scottish government, and £45 million was provided by the council. The second, completed in 2023, was funded by borrowing against future fare revenues. It came in about thirty percent cheaper per mile.

Most of the proximate causes listed above are ways in which this underlying pattern manifests itself. Profligate gold-plating, exorbitant community compensation, endless rounds of consultation, elaborate legal obligations, reliance on consultants and so on all naturally arise when none of the parties involved has any serious incentive to oppose them. If Britain wants affordable infrastructure, it needs a system in which those who make the decision to spend money also bear some of the costs of doing so.

The most conspicuous result of this cost bloat is of course that the infrastructure projects that do happen tend to be wildly expensive. But perhaps the most important effect is the projects that do not happen at all. The Treasury correctly believes that, under current conditions, public infrastructure projects in Britain will be wastefully mismanaged. Its only way of protecting public finances is thus by blocking these projects altogether. Given the means available to it, this decision is often the correct one.

But stepping back, we should recognise that many of the projects blocked by the Treasury could have excellent value for money if only they were delivered at costs that were historically and remain internationally normal. The notorious ‘feast and famine’ procurement pattern of some types of British infrastructure is also thought to be a consequence of this; the Treasury blocks routine schemes, so only schemes with exceptional political or economic support take place, which by nature arise only intermittently and unpredictably.

The theory that infrastructure costs are prone to bloating when they are paid for centrally is supported by the example of the one kind of infrastructure that has remained relatively cheap, namely roads. Despite some big failures like the Lower Thames Crossing, Britain ranks mid-table overall, a better performance than for any other infrastructure type. The reason for this is that roads directly benefit a much wider constituency than any given railway project: pretty much anyone in the nearby area rather than just the people within about one kilometre of a given station. What’s more, 94 percent of miles travelled in the UK are on roads (80 percent in private cars, and 14 percent on buses and coaches), so many more people see themselves as having a stake in the issue. The tendency for local obstructionism is thus weaker, and even national government tends not to end up with spiralling costs. For the bulk of the projects, funded (or part-funded) and delivered by local councils themselves, the effect is even stronger.

This is why the M25 could be delivered affordably through the traditional planning system, even with a spectacular 39 separate inquiries. In 1987, the first election after the M25 was finished and opened, Margaret Thatcher’s Conservatives won every constituency the road went through, including large swings in historic Labour seats like Thurrock.

But this model only works for this kind of locally uncontroversial infrastructure. For the contentious but vital projects that the country needs – railways, viaducts, bridges, nuclear power stations, tramways, wind farms – systemic reform is needed.

Why this matters

Because of bad delivery mechanisms, British infrastructure is delivered slowly and at great cost. When infrastructure is costly, less of it is delivered. To understand how bad this is, it is worth reviewing why infrastructure is important.

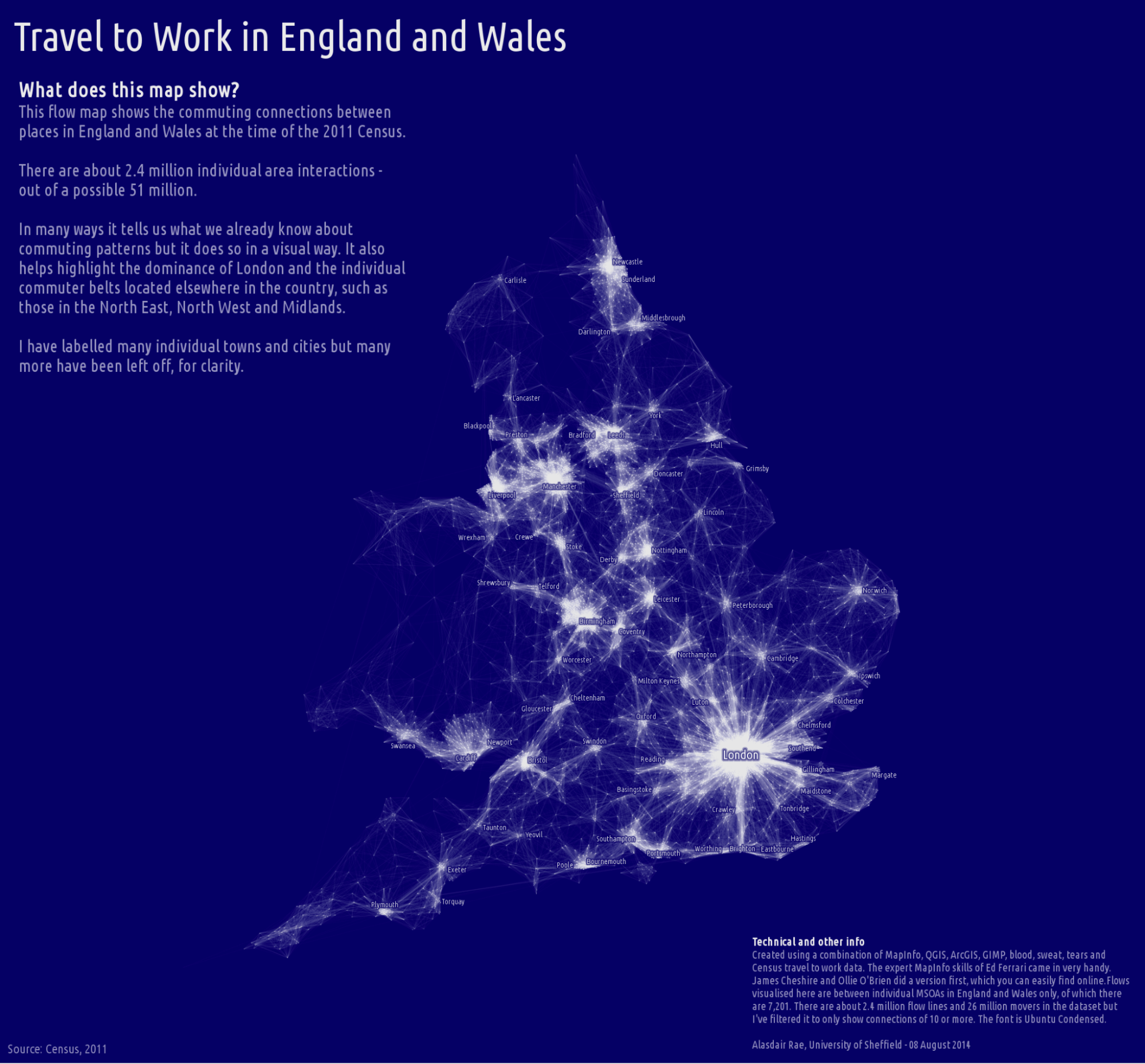

Like housing, transport infrastructure is vitally important for growth because it determines who can do which jobs. Reliable, fast transport infrastructure allows people to access a wider range of job options, and businesses to access a wider pool of talent to employ and to transport goods and services more easily. By increasing the speed you can get around, infrastructure expands the effective ‘economic size’ of a city, no less effectively than building more houses does. A ten percent increase in the number of jobs accessible per worker increases productivity 2.4 percent. A 10 percent increase in commuting speed increases the size of the labour market by 15–18 percent. Without the M25 and the suburban railway network, places like Sevenoaks, Luton, Reading, Guildford, Stansted, Chelmsford, and Woking would not be tied economically to the broader London metropolis. Companies in those places would not be able to hire from as big a pool; people living there would not be able to reach the best jobs.

It also enables both internal and cross-border trade. The Eurostar helps British services firms sell to Parisian and Brusselian companies. Heathrow is a core reason why international firms have headquarters in London. The strategic road network lets companies and consumers all over the country import and export goods through the country’s seaports.

Britain’s transport infrastructure deficit means that it forgoes these benefits. We can’t build new tramways or a metro cheaply in Birmingham, so the city is riddled with road congestion, and people choose lower-paying jobs with worse working conditions because they are easier to get to rather than because they are the best for their careers. Without the Lower Thames Crossing, road haulage to and from the Ports of Dover and Felixstowe has to move over the congested and further-flung Dartford Crossing, slowing down and raising costs for British firms looking to trade internationally.

Commuting flows in England and Wales. High quality infrastructure

is the reason why so many can commute miles to bigger job markets

than where they live.

Commuting flows in England and Wales. High quality infrastructure

is the reason why so many can commute miles to bigger job markets

than where they live.

A second and vitally important benefit from all infrastructure is that, without it, locals oppose new homes near them. If there is already congestion on the roads they use, or they are already unable to get a seat on their morning train, they have a powerful reason to oppose new development. Thus, new infrastructure enables new homes and makes them politically much easier to build. The infrastructure deficit makes them correspondingly harder.

In some cases, the infrastructure deficit is literally making new development in Britain unlawful. Because Britain has not built a new reservoir for thirty years, there are chronic water shortages in the East of England. This means that the Environment Agency has begun to block new housing on the basis that it could only be supplied with water through drawing on environmentally valuable chalk streams. The result is that it is virtually unlawful for the Government to permit the expansion of Cambridge, leading to the gradual strangulation of Britain’s biotech industry. The same problem will compromise any new town scheme that the Government wants to initiate in large parts of the country.

This chapter has focussed on the deficit in transport infrastructure. But there is another infrastructure deficit that is at least as grave: energy. Energy costs are rising steeply in Britain, starving energy-intensive industries and undermining living standards. This disastrous trend has deep causes, to which we turn in the next chapter.

Britain: the first energy superpower6

Between 1550 and 1700, Britain transformed from a normal European country, depending on peat and wood for heating homes, to by far Europe’s biggest coal producer and consumer. Every coal-producing region upped its output by at least ten times. By 1640, Britain was mining around 1.5 million tonnes of coal per year, about three times as much as the rest of Europe put together.

This energy boom set off growth in an uncountable number of other industries. The Firth of Forth started exporting salt all over Europe, including to salt-producing regions like the Low Countries. Britain’s coal allowed it to become a major producer of soap, candles, starch, saltpetre (for gunpowder), alum and copperas (for fixing dyes into clothes), as well as being used in brewing, dyeing, making malt, baking bread, making tiles and bricks, forging and working iron, copper, brass, lead, silver, and tin, glass, and bending staves and beams for barrels and ships.

It went much further than these cases. Coal is used to produce lime. Cheaper and more abundant coal meant dramatically more lime. Dramatically more lime meant dramatically more fertiliser, which meant much more productive grain fields. More salt meant more meat and fish preservation, raising the productivity of pasture land. Peatlands and heaths were no longer necessary for fuel, so they could be converted to arable land or pastures.

All of this meant more muscle power – horses and oxen – which powered the earliest machinery. These animals were put to an enormous range of uses, and their extreme proliferation in Britain wowed Europeans throughout the 1600s and 1700s. And it meant more human muscle power. The average Briton ate something like 600 calories more per day than the average Frenchman, and was about five centimetres taller.

All this is to say that Britain was the first energy superpower, and it built its global economic dominance on the back of, above all, cheaper and more abundant energy than anywhere else. Until the 1920s it produced more energy per person than any other country. Until the 1960s it produced more energy than any other country but America.

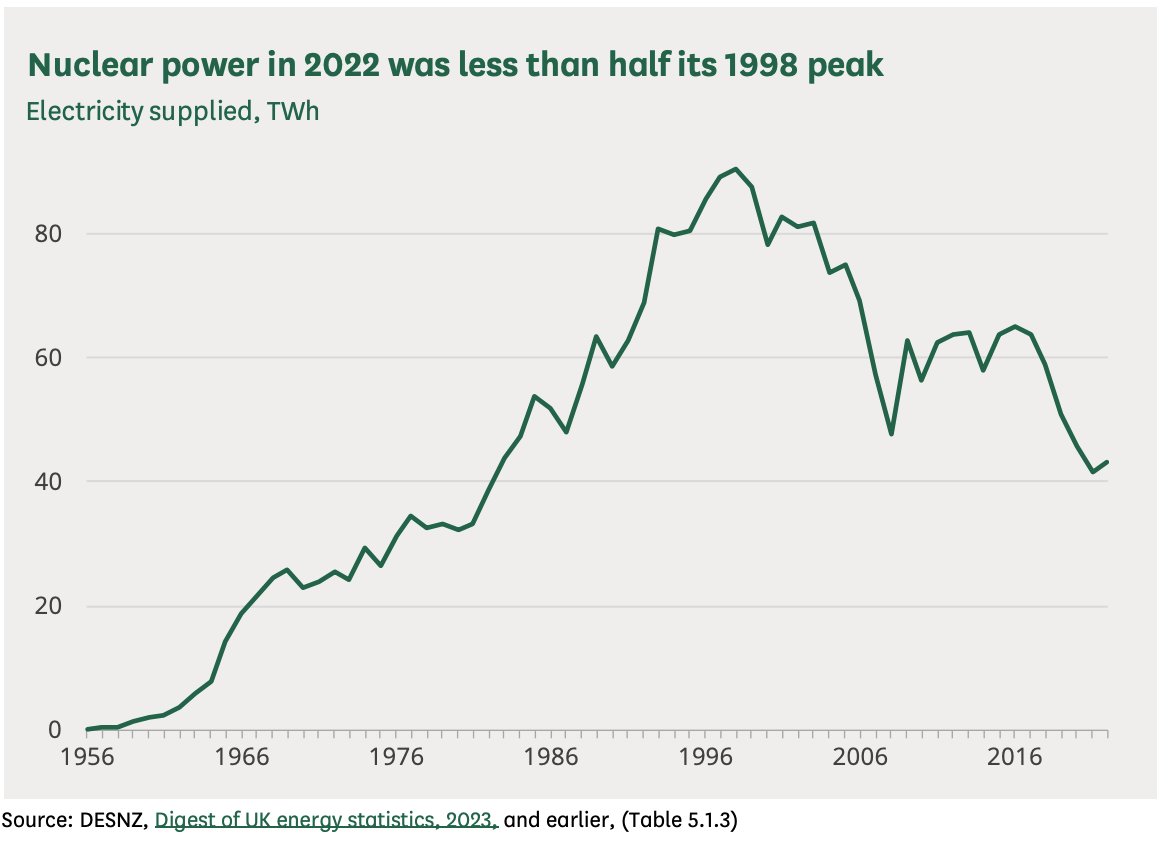

As coal’s enormous downsides were recognised – horrific lung issues for those mining it and inhaling its fumes, as well as devastating smogs – in 1956 we became the first of all countries to move to the energy technology of the future: nuclear. In its early years, Britain was the world leader in nuclear power. In 1965 we had 21 nuclear reactors, compared to 19 in the rest of the world combined.

Uranium’s energy density – three million times higher than coal – suggested that it could be much cheaper as a source of power, since it would not necessitate so much mining and transportation. We didn’t realise then that nuclear power could also help us to avoid damaging climate change. But had we continued down that path, we would have inadvertently decarbonised, like France.

If we had only kept pace with the rate of nuclear rollout that we had between 1956 and 1998, by extending the lifetimes of our older plants and adding new ones, today we would be producing around 150 TWh of nuclear power per year, or around 50 percent of our total current electricity generation. But we did not. Nuclear power in Britain is now half of what it was at its peak, and energy costs today are higher than they have been for a century.

Energy costs

There are good reasons to want the UK to have a large, productive industrial base. But any industrial strategy aimed at doing this must first reckon with the enormous rises in energy prices for UK businesses since the mid-2000s. The industrial price of electricity rose by 153 percent between 2004 and 2021, adjusted for inflation. It rose even more brutally again after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Very large industrial customers (those consuming 70,000–150,000 megawatt-hours of electricity every six months) paid more than twice as much in Britain (13.79p per kilowatt-hour) for electricity in 2021 as their counterparts in France did (6.62p per kilowatt-hour), and, again, the gap has grown since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Even if energy costs eventually fall back to normal pre-war levels, those are still much more expensive in real terms than twenty years ago. Fixing this has to be step one for any serious industrial strategy.

High energy costs are a problem across the developed world. Energy consumption per capita in even the relatively fast-growing United States has flatlined from the early 1970s oil crisis onwards. But things are much worse here.

The UK’s energy use per person has long been far behind that of the United States, but it fell behind both France and Germany in the post-war era. Despite moderate improvements under Thatcher, it has slid since the mid-2000s to fall further below other countries.

Britain’s energy use per unit of GDP is now the lowest in the G7, and is lower than nearly every region and every non-tax-haven in both Europe and the OECD. By many measures, Britain is the most energy-starved nation in the developed world.